Origin Story

Clouds form when moist air rises and cools, causing water vapor to condense into tiny droplets or ice crystals. This process occurs naturally in Earth's troposphere, where varying atmospheric conditions give rise to diverse cloud forms. The systematic classification of clouds began in the early 19th century, notably with Luke Howard's pioneering nomenclature, which laid the foundation for the modern meteorological taxonomy maintained by the World Meteorological Organization.

Classification

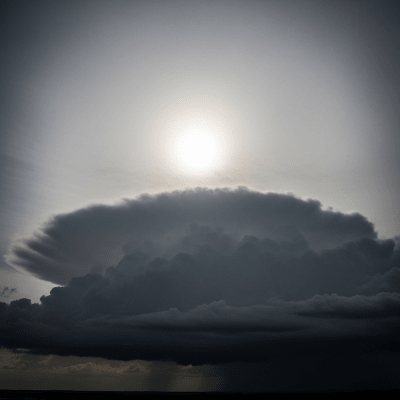

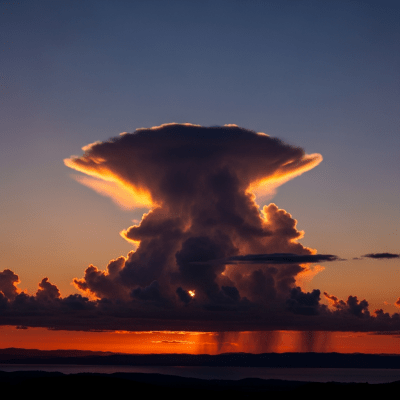

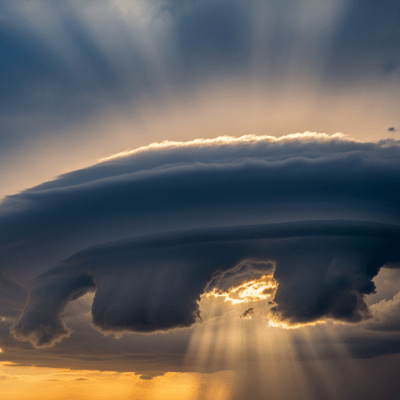

The classification of clouds follows a hierarchical system centered on morphological features. At the top level are genera—broad categories such as Cirrus, Cumulus, and Stratus—distinguished primarily by their shape and altitude. These are further divided into species based on internal structure and form, then into varieties describing transparency or arrangement. Supplementary features and accessory clouds modify or accompany these main types, while altitude families (high, middle, low, vertical) provide an additional organizational layer reflecting typical cloud heights.

Appearance or Form

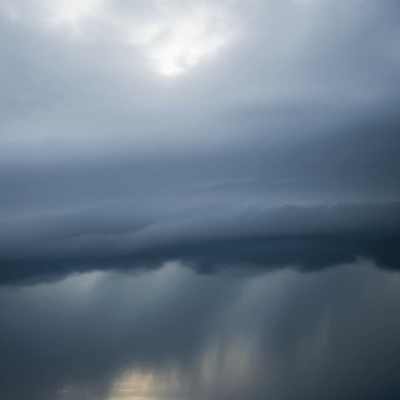

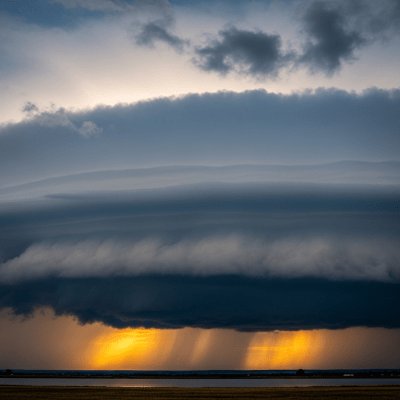

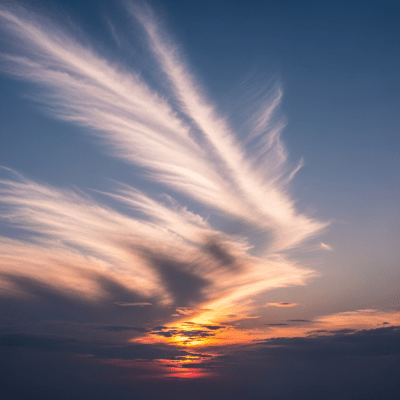

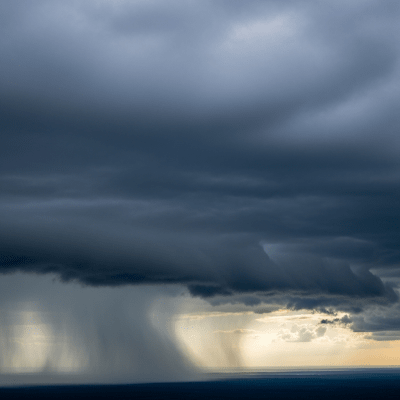

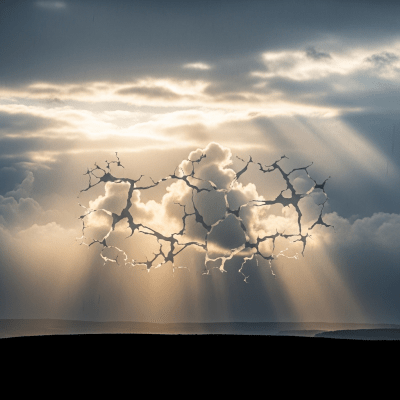

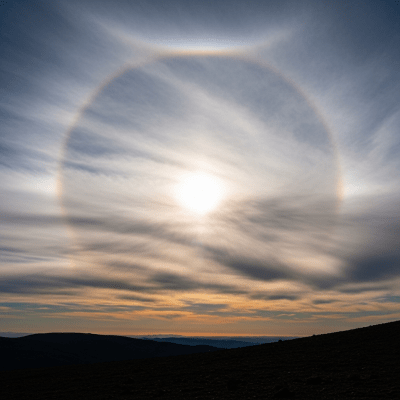

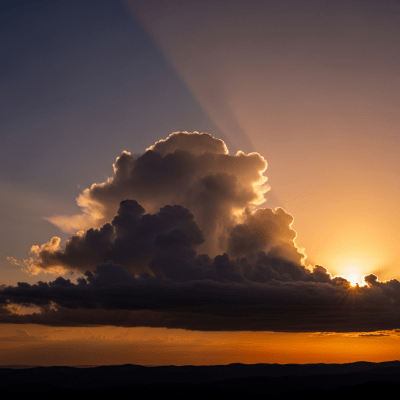

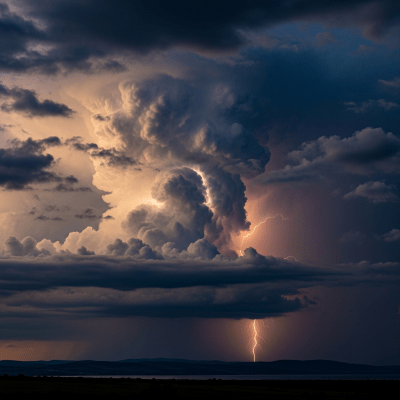

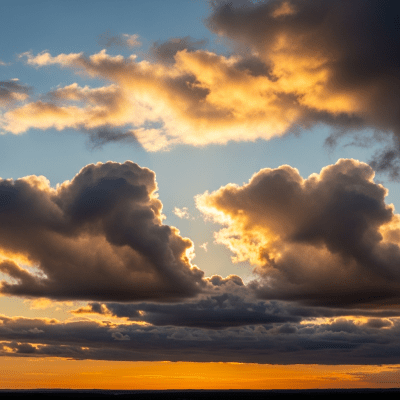

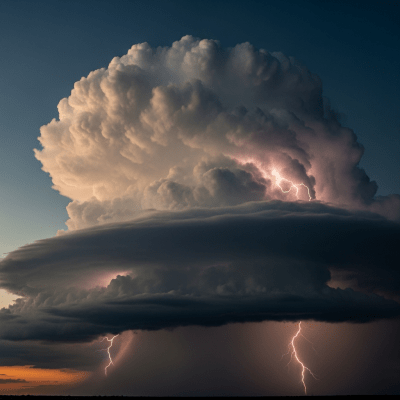

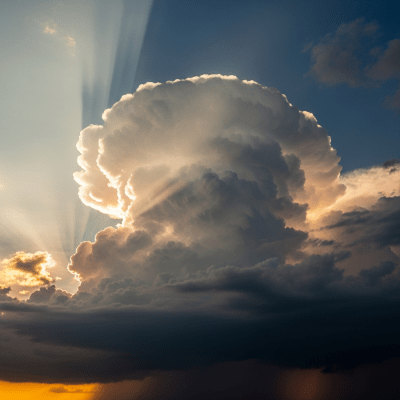

Clouds exhibit a wide range of visual forms, from the wispy, delicate strands of high-altitude cirrus to the towering, dense masses of cumulonimbus. Their appearance depends on factors like altitude, moisture content, and atmospheric dynamics. Common descriptors include puffy, layered, or fibrous textures, with edges ranging from sharp and well-defined to diffuse. Some clouds display striking supplementary features such as mammatus pouch-like formations or virga trails of evaporating precipitation, enhancing their distinctive visual character.

Behavior or Usage

Clouds play a vital role in Earth's weather and climate systems by regulating radiation, precipitation, and atmospheric circulation. Meteorologists and aviators rely on cloud classification to forecast weather, identify hazards like turbulence or icing, and communicate conditions effectively. Beyond operational use, clouds serve as indicators of atmospheric processes, helping scientists understand convection, frontal systems, and moisture transport. Their predictable patterns also support educational efforts and citizen science initiatives in weather observation.