Populus

Poplars are fast-growing, deciduous trees of the genus Populus, valued for their straight trunks, adaptability, and wide-ranging economic and ecological uses across the Northern Hemisphere.

Poplars are fast-growing, deciduous trees of the genus Populus, valued for their straight trunks, adaptability, and wide-ranging economic and ecological uses across the Northern Hemisphere.

The genus Populus was first formally described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, with evolutionary roots spanning temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Poplars have diversified into approximately 25–35 species, thriving along rivers, floodplains, and open woodlands. Their natural range extends from North America through Europe and Asia, and centuries of cultivation have produced numerous hybrids and clones for forestry, landscaping, and environmental restoration.

Poplars belong to the family Salicaceae, sharing close botanical ties with willows (Salix spp.). They are classified as angiosperms (flowering plants), within the order Malpighiales. The genus Populus encompasses several species commonly known as poplars, aspens, and cottonwoods, reflecting regional naming conventions. Their taxonomic path is: Kingdom Plantae > Division Magnoliophyta > Class Magnoliopsida > Order Malpighiales > Family Salicaceae > Genus Populus.

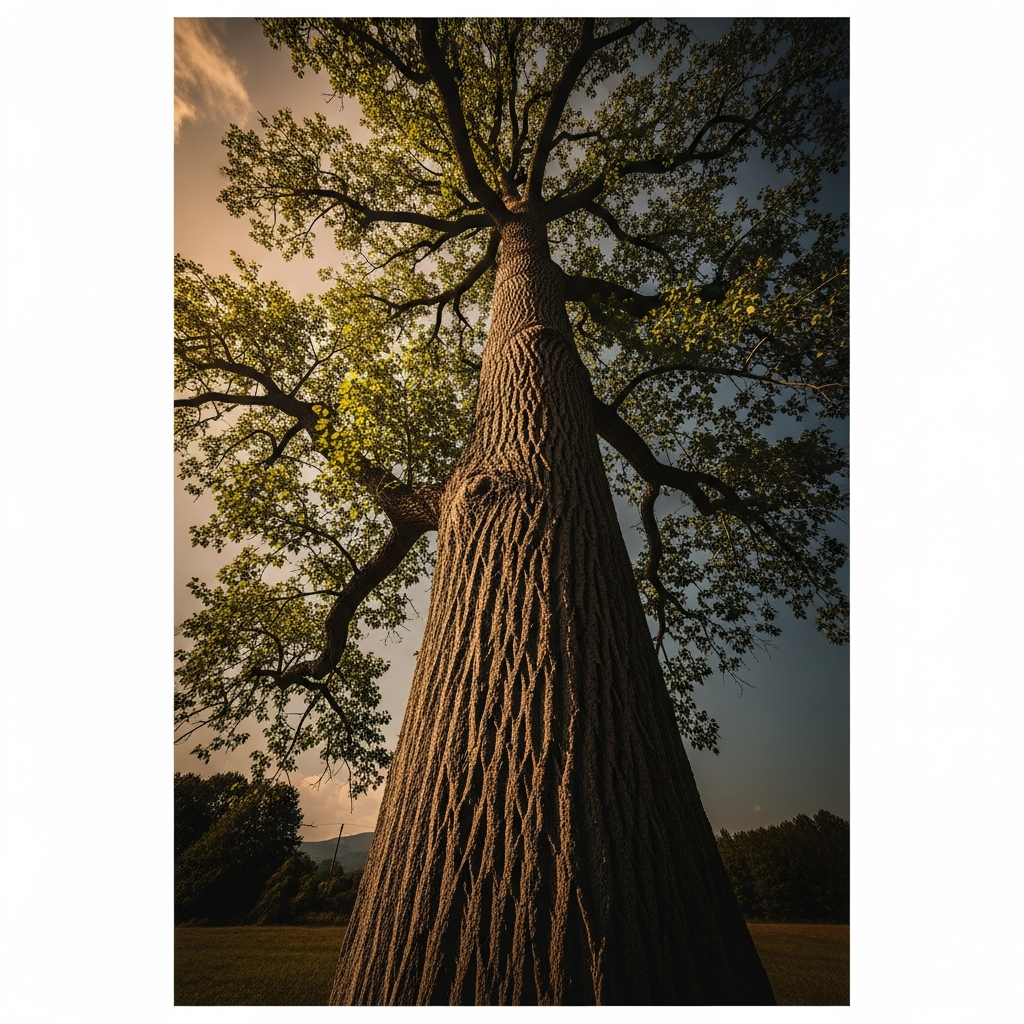

Poplars are medium to large trees, typically rising 15–50 meters tall. Their straight, slender trunks support broad crowns of simple, alternate leaves, which may be triangular, ovate, or lance-shaped depending on species. Young bark is smooth and pale, maturing into a more fissured, textured surface. In spring, poplars produce long, dangling catkins—clusters of tiny flowers that sway in the breeze. The trees are dioecious, meaning male and female flowers grow on separate individuals, and their foliage often shimmers in the wind, especially in aspens.

Poplars are renowned for their rapid growth and ability to colonize disturbed or wet soils. They propagate vigorously via root suckers, forming dense stands. Humans utilize poplars extensively in forestry for timber, pulpwood, and biomass, and in environmental applications such as windbreaks, erosion control, and phytoremediation. Their adaptability makes them popular for urban landscaping and restoration projects, and many clones are bred for improved disease resistance and specific growth traits.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtPoplars have long featured in art, literature, and folklore, often symbolizing resilience, rapid change, or the fleeting nature of life. Their shimmering leaves and stately form have inspired poets and painters, while their presence along rivers and roadsides marks boundaries and transitions in landscapes. In some cultures, poplars are associated with healing and renewal, reflecting their role in environmental restoration and traditional medicine.

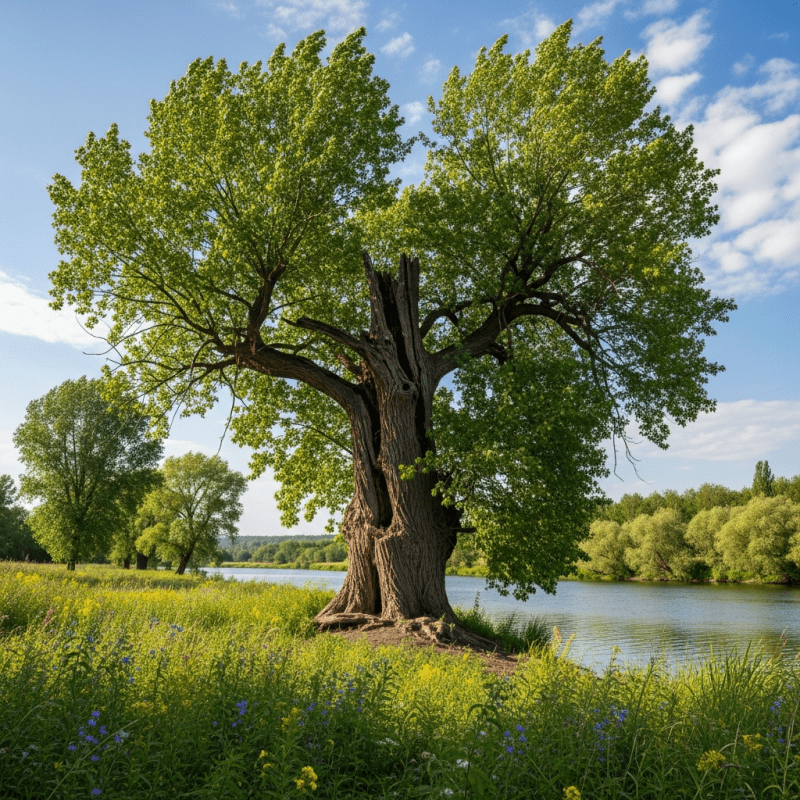

Poplars play a vital role in riparian and floodplain ecosystems, stabilizing soils and providing habitat for birds, insects, and mammals. Their rapid growth and dense root systems help control erosion, while fallen leaves enrich soil fertility. Poplar stands support diverse wildlife, including cavity-nesting birds and pollinators attracted to their catkins. In managed landscapes, poplars contribute to windbreaks and act as natural filters for water and soil contaminants.

Poplars are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, with natural populations spanning North America, Europe, and Asia. They favor moist soils along rivers, lakes, and floodplains, but are highly adaptable and often found in open woodlands, urban parks, and disturbed sites. Cultivated hybrids extend their range into plantations and restoration areas worldwide, thriving in climates with cold winters and warm summers.

Poplars are easy to cultivate, preferring full sun and moist, well-drained soils. They can be propagated by seed or vegetatively via root cuttings and suckers. Regular monitoring for pests (such as poplar borers) and fungal diseases (like leaf rust) is important, especially in monoculture plantations. Pruning helps maintain shape and health, and selecting disease-resistant clones improves longevity. Poplars grow quickly but may require supplemental irrigation in dry climates, and their roots can be invasive near structures.

Major threats to wild poplar species include habitat loss, river regulation, hybridization with cultivated clones, and susceptibility to pests and diseases. Some species, such as black poplar, are considered threatened in parts of their range. Conservation efforts focus on habitat restoration, genetic diversity preservation, and planting native or disease-resistant varieties. Monitoring and controlling invasive hybrids is also crucial for maintaining wild populations.

Poplars are economically important for timber, used in plywood, pallets, matchsticks, and furniture. Their fast growth makes them ideal for pulpwood in paper manufacturing and as a renewable biomass source for energy. Environmental uses include windbreaks, erosion control, and phytoremediation of contaminated soils. While not typically consumed, poplar extracts have traditional medicinal applications for anti-inflammatory purposes in some cultures.

In folklore, poplars often symbolize resilience, transformation, and the passage of time. Their trembling leaves are said to whisper secrets or foretell change, and their presence along roads and rivers marks journeys and boundaries. In some traditions, poplars are associated with healing and renewal, reflecting their ability to restore degraded landscapes and their use in traditional remedies.