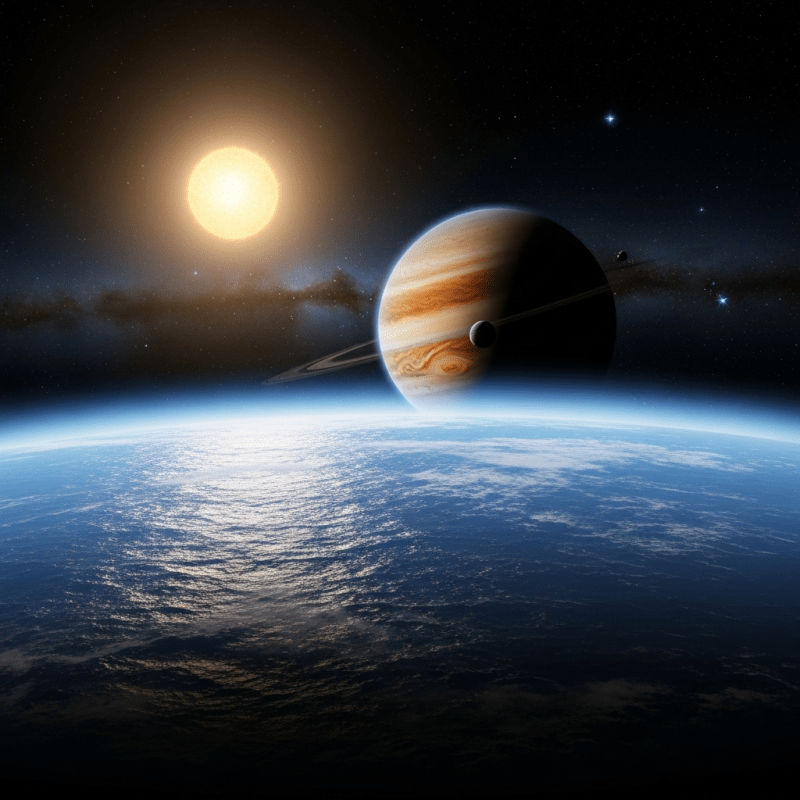

Ocean planet

An ocean planet is a type of planet dominated by a global, deep liquid-water ocean that may cover its entire surface, often with no exposed landmasses.

An ocean planet is a type of planet dominated by a global, deep liquid-water ocean that may cover its entire surface, often with no exposed landmasses.

The concept of the ocean planet emerged in the early 2000s through theoretical models of planetary formation and composition, notably introduced by Léger et al. (2004). These planets are thought to form beyond the snow line by accumulating large amounts of water ice before migrating closer to their stars, shaping their volatile-rich nature. Since then, the idea has gained traction in both scientific and popular discussions, supported by institutions like ESA and NASA, though it remains a theoretical class without formal recognition by the IAU.

Ocean planets belong to a distinct compositional class within planetary taxonomy characterized by a high fraction of water and volatiles dominating their mass and surface. They are often considered a subclass of volatile-rich planets and may overlap in mass and radius with mini-Neptunes or sub-Neptunes, making their classification nuanced. Their defining trait is the presence of a vast, global ocean rather than exposed solid surfaces typical of terrestrial planets.

These planets appear as spherical bodies entirely covered by a deep, global ocean that can extend tens to hundreds of kilometers beneath the surface. The surface is liquid water, potentially with underlying layers of high-pressure ice formed by immense oceanic depths. Unlike Earth, ocean planets may lack any exposed land, presenting a seamless watery expanse under various atmospheric conditions.

Ocean planets primarily function as natural worlds with unique environments dominated by water. While direct human interaction remains hypothetical, their study informs our understanding of planetary formation, volatile retention, and potential habitability. They may exhibit diverse atmospheric behaviors, including water vapor-rich envelopes or hydrogen-dominated layers, influencing climate and surface conditions. Their presence challenges models of planet habitability and guides observational strategies in exoplanet research.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtOcean planets captivate imagination as "water worlds" or "aquaplanets," inspiring science fiction and popular culture depictions of endless seas and alien marine ecosystems. They symbolize the possibility of life beyond Earth in environments vastly different from terrestrial landscapes. While not formally recognized in astronomical nomenclature, ocean planets have become a staple concept in exoplanetary science communication and speculative narratives about habitable worlds.

Ocean planets do not have strict orbital constraints and can exist at various distances from their host stars. Their formation beyond the snow line suggests initial orbits far from the star, followed by possible inward migration. Their habitability and ocean state depend heavily on equilibrium temperature, which varies with orbital distance and stellar radiation. Because of this, ocean planets may be found in a range of orbital environments, from temperate zones to closer, hotter orbits.

Typically, ocean planets have masses around 5 Earth masses and radii near 2 Earth radii, with densities near 2 grams per cubic centimeter, reflecting their high water and volatile content. Their morphology is that of a spherical body enveloped by a deep liquid ocean, potentially hundreds of kilometers thick. Their internal structure may include layers of high-pressure ice beneath the ocean. These properties distinguish them from rocky terrestrial planets and gaseous mini-Neptunes.

Ocean planets generally possess atmospheres, which may range from thin to thick envelopes dominated by water vapor, hydrogen, and other volatiles. The atmospheric composition is highly model-dependent and challenging to observe directly. These atmospheres influence surface conditions, climate, and potential habitability, and may vary widely depending on the planet's temperature and formation history.

Ocean planets remain theoretical constructs with no direct exploration missions to date. Their study relies on theoretical modeling, mass-radius measurements of exoplanets, and atmospheric characterization through remote sensing. Notable candidates like GJ 1214 b have been observed by space telescopes, fueling ongoing debate about their nature. Future missions aiming to characterize exoplanet atmospheres may provide clearer evidence for ocean planets.

Habitability on ocean planets depends on maintaining temperatures that allow liquid water, typically between 273 and 373 K. Their global oceans provide a vast reservoir of water, a key ingredient for life as we know it. However, thick atmospheres, high pressures, and lack of land may pose challenges for life’s emergence or sustainability. Some models suggest subsurface oceans under ice layers could harbor life, while others consider "hot ocean planets" with steam atmospheres as less hospitable. Overall, ocean planets remain promising but uncertain candidates in the search for habitable worlds.