Hot Jupiter

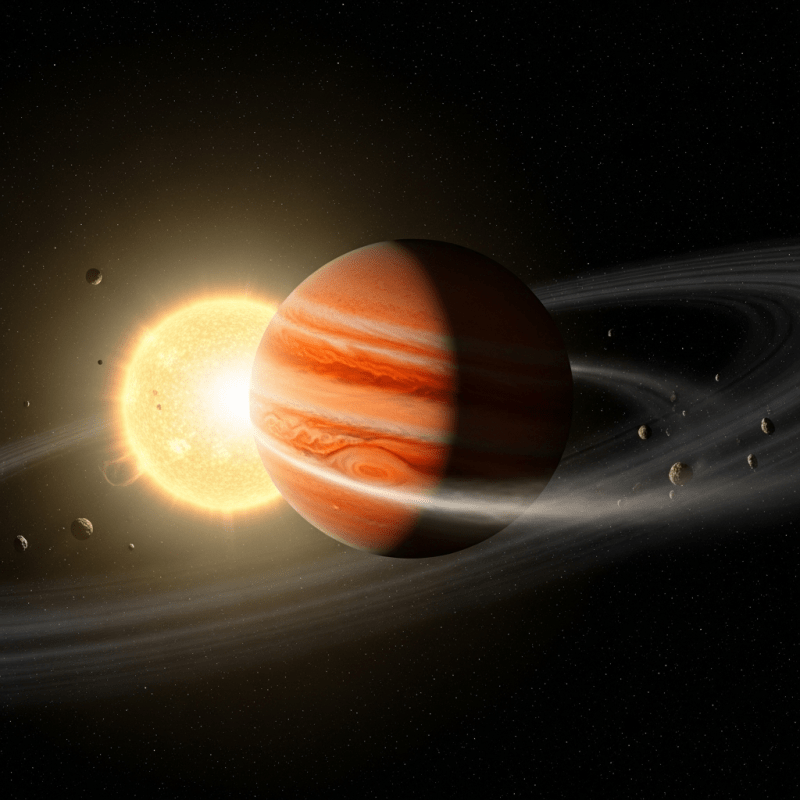

A Hot Jupiter is a gas giant exoplanet similar in mass to Jupiter that orbits extremely close to its host star, resulting in very high surface temperatures.

A Hot Jupiter is a gas giant exoplanet similar in mass to Jupiter that orbits extremely close to its host star, resulting in very high surface temperatures.

The concept of the Hot Jupiter emerged in the mid-1990s after the groundbreaking discovery of 51 Pegasi b, the first exoplanet found orbiting a Sun-like star. This unexpected class challenged traditional planetary formation theories by revealing that massive gas giants could migrate inward from their birthplaces beyond the snow line to settle in scorching, close-in orbits.

Hot Jupiters belong to the gas giant category of planets, distinguished by their large masses and predominantly hydrogen-helium compositions. They are further defined by their short orbital distances—typically less than 0.1 astronomical units—and rapid orbital periods under 10 days, setting them apart from colder, more distant gas giants.

These planets resemble Jupiter in size and mass but often exhibit inflated radii due to intense stellar irradiation. Their morphology is dominated by thick, gaseous envelopes composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, sometimes expanding to twice Jupiter's radius. Their atmospheres can be visually striking with signatures of sodium, potassium, and, in the hottest cases, exotic compounds like titanium oxide and vanadium oxide.

Hot Jupiters primarily interact with their environment through their close proximity to their stars, which drives extreme atmospheric heating and escape. Their large sizes and short orbital periods make them prime targets for transit and radial velocity detection methods, providing critical insights into planetary migration and atmospheric physics.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtHot Jupiters have captured public imagination as exotic worlds vastly different from anything in our Solar System. Their discovery reshaped scientific narratives about planet formation and migration, inspiring numerous artistic and literary works exploring alien worlds orbiting perilously close to their suns.

Hot Jupiters orbit extremely close to their stars, usually within 0.015 to 0.05 astronomical units, completing orbits in just 1 to 10 Earth days. Their orbits tend to be nearly circular due to tidal forces, with eccentricities often close to zero. This proximity results in intense stellar radiation and high equilibrium temperatures typically around 1500 K, with some ultra-hot variants exceeding 2200 K.

These planets generally have masses ranging from about 0.3 to 10 Jupiter masses and radii between 1.0 and 2.0 Jupiter radii, often inflated by stellar heating. Their densities are lower than Jupiter’s, sometimes as low as 0.2 grams per cubic centimeter. Composed primarily of hydrogen and helium, their internal structures resemble those of gas giants but are influenced by their extreme environments.

Hot Jupiters possess thick atmospheres dominated by hydrogen and helium, enriched with trace elements like sodium, potassium, and water vapor. In the hottest examples, molecules such as titanium oxide and vanadium oxide have been detected, which can create temperature inversions. Their atmospheres often experience escape and inflation due to intense stellar irradiation, leading to extended, sometimes escaping, gaseous envelopes.

Since the discovery of 51 Pegasi b in 1995, Hot Jupiters have been extensively studied through ground- and space-based telescopes. Missions like Hubble and Spitzer have characterized their atmospheres, while surveys such as Kepler and TESS have identified thousands of candidates. These observations have deepened understanding of planetary migration, atmospheric composition, and star-planet interactions.

Hot Jupiters are inhospitable to life due to their extreme temperatures, intense radiation, and lack of solid surfaces. Their close orbits cause atmospheric stripping and tidal locking, creating harsh environments unsuitable for known biological processes. While they do not support habitability themselves, studying them informs broader planetary science and the conditions that shape planetary systems.