Cold Jupiter

A Cold Jupiter is a gas giant planet similar in mass and size to Jupiter, orbiting far from its host star with a low equilibrium temperature.

A Cold Jupiter is a gas giant planet similar in mass and size to Jupiter, orbiting far from its host star with a low equilibrium temperature.

The term "Cold Jupiter" arose in the early 2000s from exoplanet studies distinguishing these distant gas giants from their close-in counterparts, the Hot Jupiters. Inspired by our Solar System's Jupiter and Saturn, the classification gained traction through planetary formation research and observational catalogs, notably by the IAU and NASA Exoplanet Archive, reflecting planets that form beyond the snow line in protoplanetary disks.

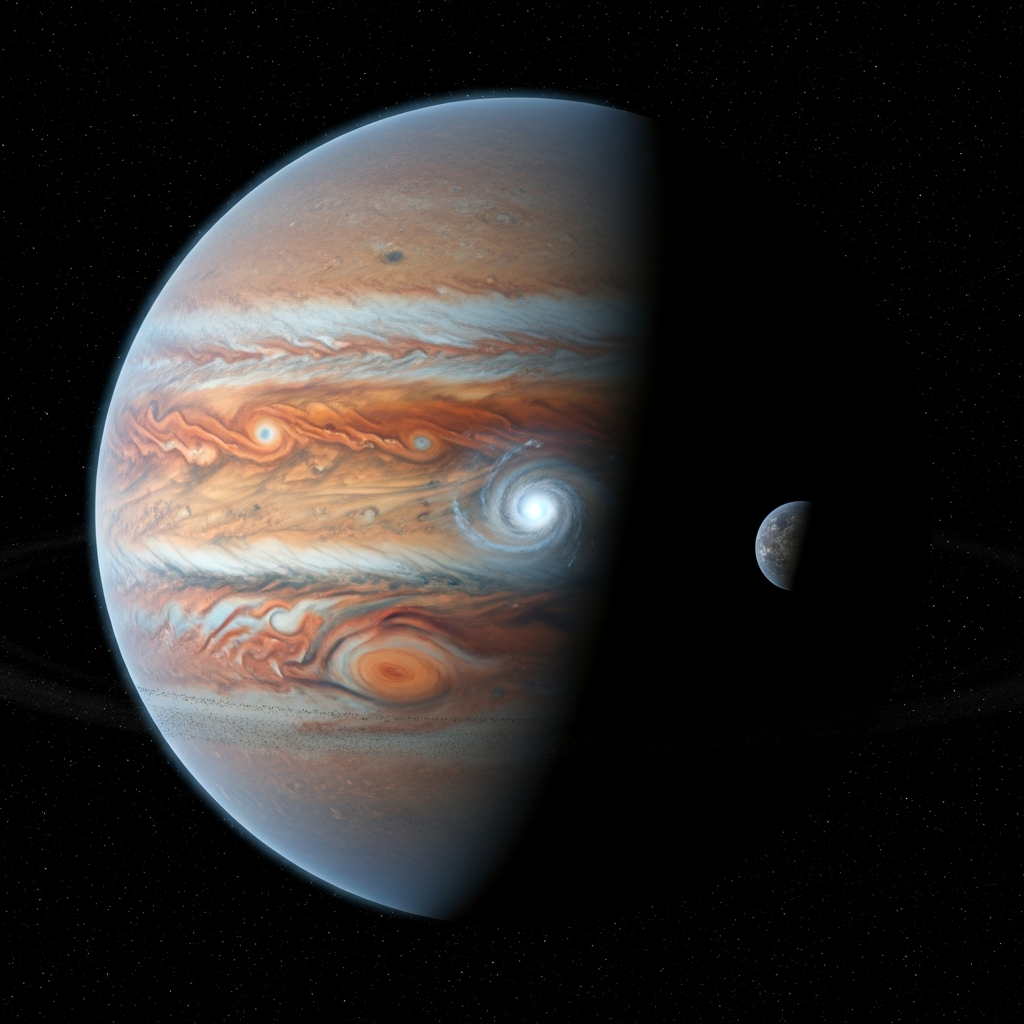

Cold Jupiters belong to the gas giant category, characterized by their large masses—typically around one Jupiter mass—and substantial hydrogen-helium envelopes. They are distinguished from Hot Jupiters by their wide orbits and low temperatures, fitting within the broader family of long-period gas giants that shape planetary system architectures.

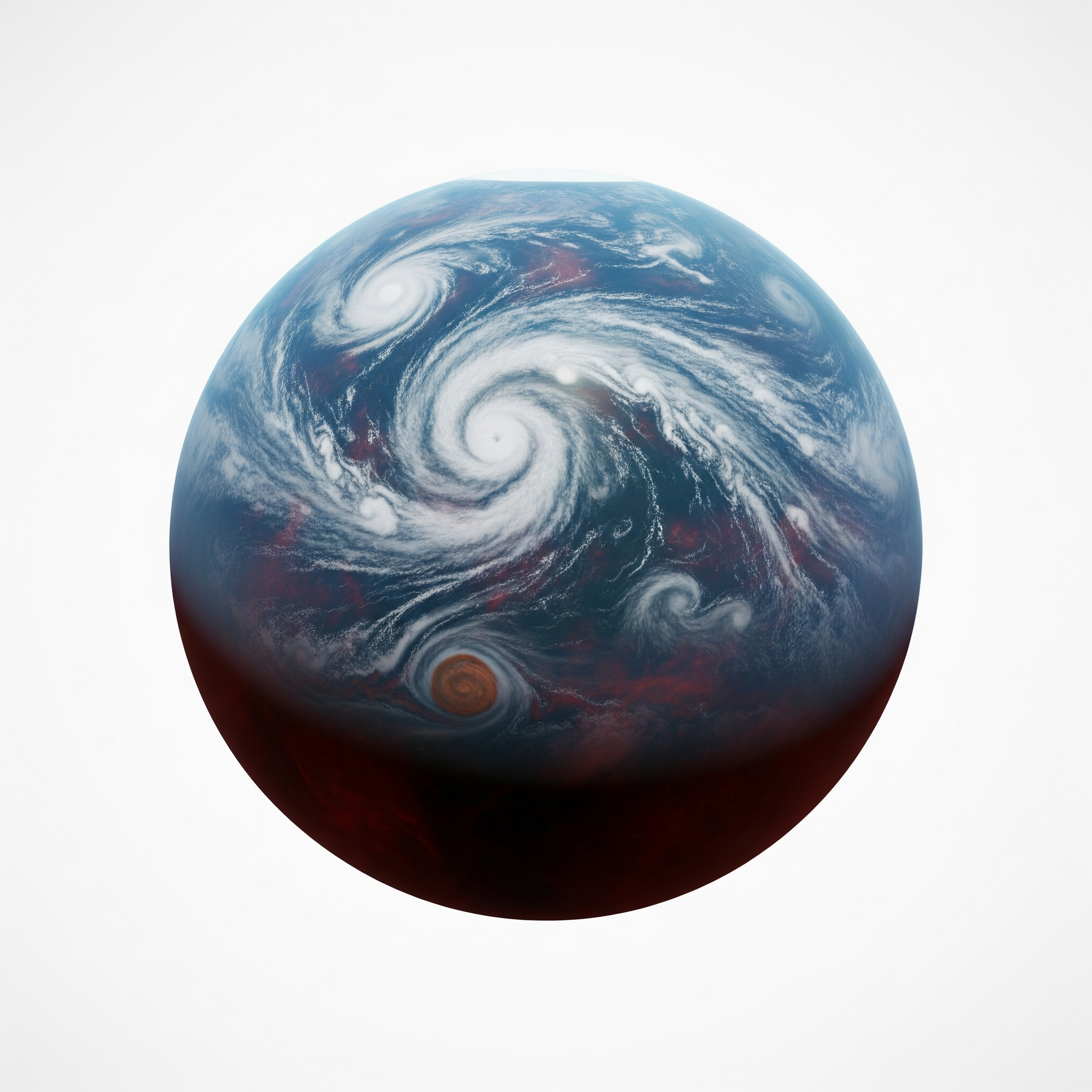

Visually, Cold Jupiters resemble Jupiter with a radius close to one Jupiter radius. They possess thick, multi-layered atmospheres dominated by hydrogen and helium, often adorned with cloud decks of ammonia and water ice. Their appearance is shaped by low temperatures that allow volatile compounds to condense, giving them a muted, banded look with subtle hues influenced by atmospheric chemistry.

Cold Jupiters play a crucial role in the dynamics of their planetary systems, influencing the formation and orbital evolution of inner planets. While not directly useful to humans, their presence helps astronomers understand planet formation processes and system stability. They are primarily studied through indirect detection methods such as radial velocity and direct imaging, due to their long orbital periods and low transit probabilities.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtCold Jupiters, epitomized by Jupiter itself, have long inspired human culture, symbolizing power and grandeur in mythology and art. In modern astronomy, they represent the archetype of giant planets in distant orbits, shaping narratives about planetary system diversity and the potential for Earth-like worlds shielded by such giants.

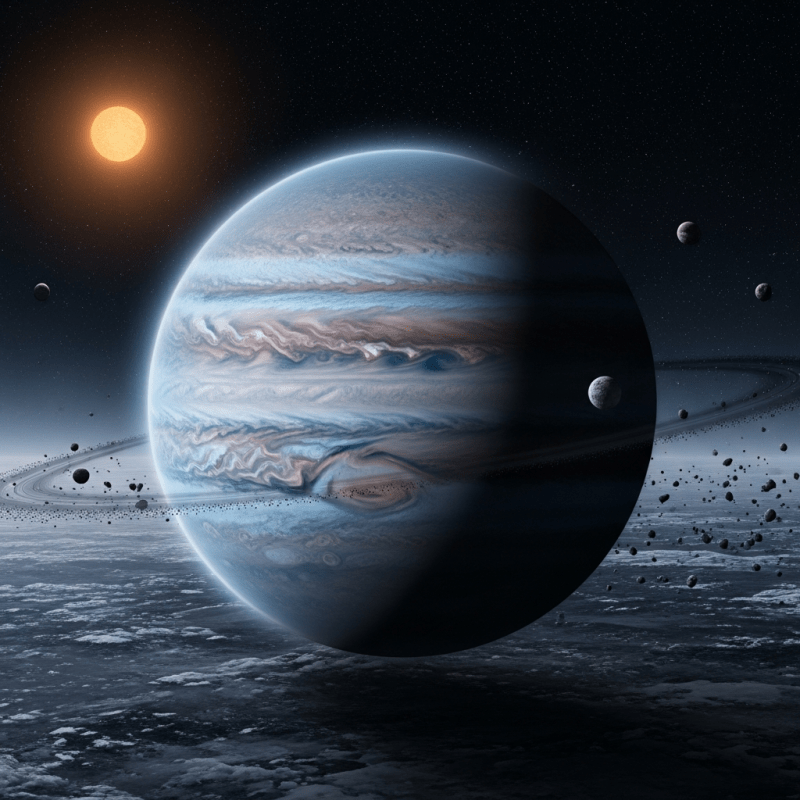

Cold Jupiters orbit their stars at large distances, typically around 5 astronomical units or more. Their orbital periods span years to decades, exemplified by Jupiter's 11.86-year orbit. Their orbits tend to be near-circular with low eccentricity, and their low insolation results in equilibrium temperatures generally below 150 Kelvin, reflecting their position well beyond the snow line.

Cold Jupiters have masses around one Jupiter mass (approximately 318 Earth masses) and radii close to one Jupiter radius (~71,492 km). Their mean densities average about 1.3 grams per cubic centimeter, reflecting a composition dominated by hydrogen and helium with a smaller rocky and icy core. Their morphology includes a dense core enveloped by a thick gaseous atmosphere.

These planets possess extensive atmospheres rich in hydrogen and helium, with trace gases such as methane, ammonia, and water vapor. Their low temperatures foster the formation of cloud layers composed of ammonia and water ice, creating complex weather patterns and layered atmospheric structures that contribute to their distinctive appearance.

Our understanding of Cold Jupiters began with Solar System exploration missions studying Jupiter and Saturn. In recent decades, advances in radial velocity and direct imaging techniques have enabled the discovery of exoplanetary Cold Jupiters, such as HD 154345 b. These findings have expanded knowledge of planetary system architectures and formation theories.

Cold Jupiters themselves are inhospitable to life due to their gaseous composition and frigid temperatures. However, their presence may indirectly support habitability by stabilizing inner planetary orbits and shielding terrestrial planets from excessive cometary impacts, potentially fostering conditions favorable to life closer to the host star.