Carbon planet

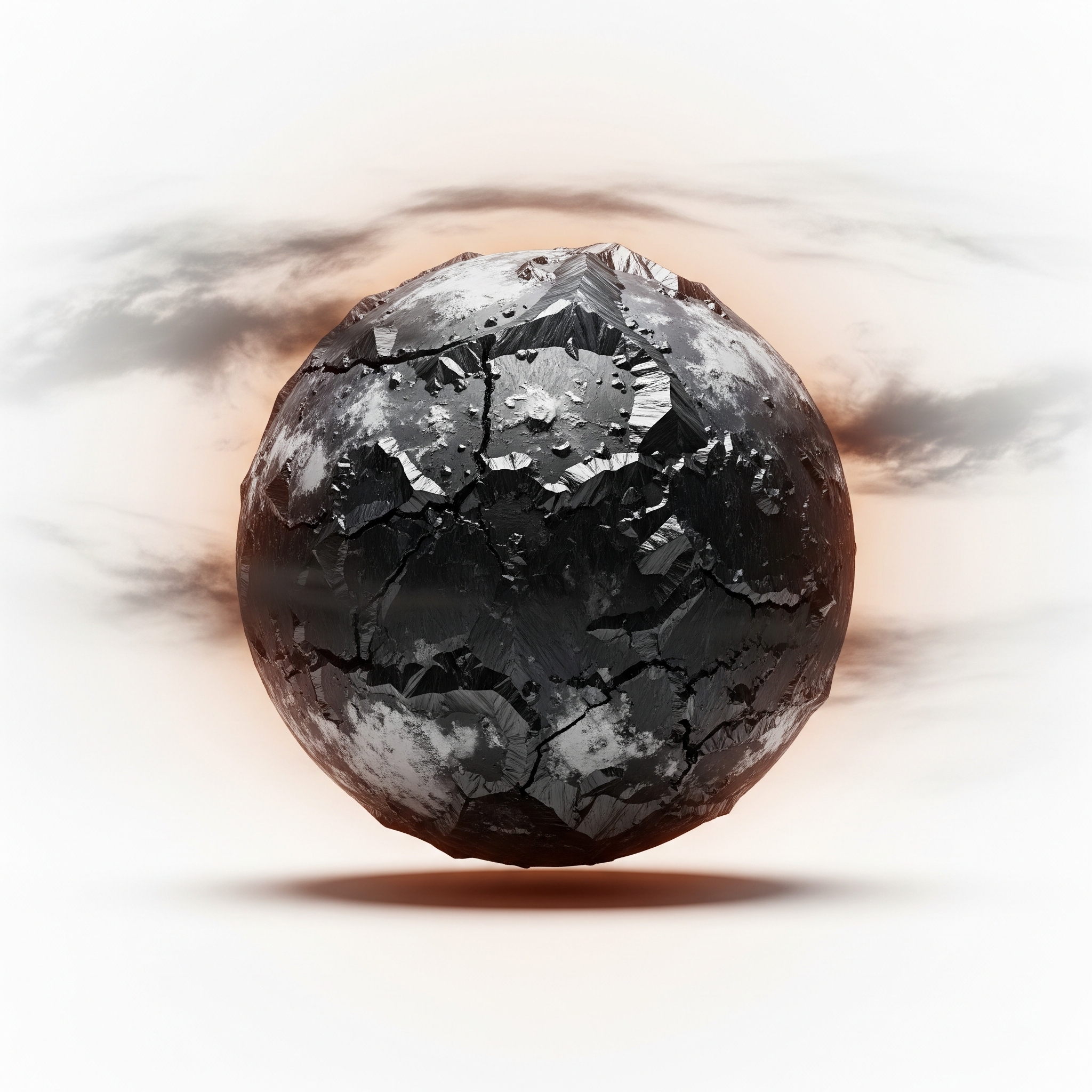

A carbon planet is a theoretical type of terrestrial planet whose bulk composition is dominated by carbon-rich materials such as carbides, graphite, and diamond, rather than the silicate minerals typical of Earth-like worlds.

A carbon planet is a theoretical type of terrestrial planet whose bulk composition is dominated by carbon-rich materials such as carbides, graphite, and diamond, rather than the silicate minerals typical of Earth-like worlds.

Carbon planets are predicted to form in protoplanetary disks where the carbon-to-oxygen ratio exceeds one, creating environments rich in carbon compounds instead of silicates. This concept was first introduced in the early 2000s by astrophysicists exploring alternative planetary chemistries, notably Marc Kuchner and Sara Seager, who proposed these exotic worlds could arise around carbon-rich stars or in oxygen-poor regions of planetary systems.

Classified within the terrestrial planet category, carbon planets represent an exotic subclass distinguished by their carbon-dominated mineralogy. Unlike typical rocky planets composed mainly of silicates and metals, carbon planets are theorized to contain abundant silicon carbide, graphite, and diamond, setting them apart from standard terrestrial or ocean planets in planetary taxonomy.

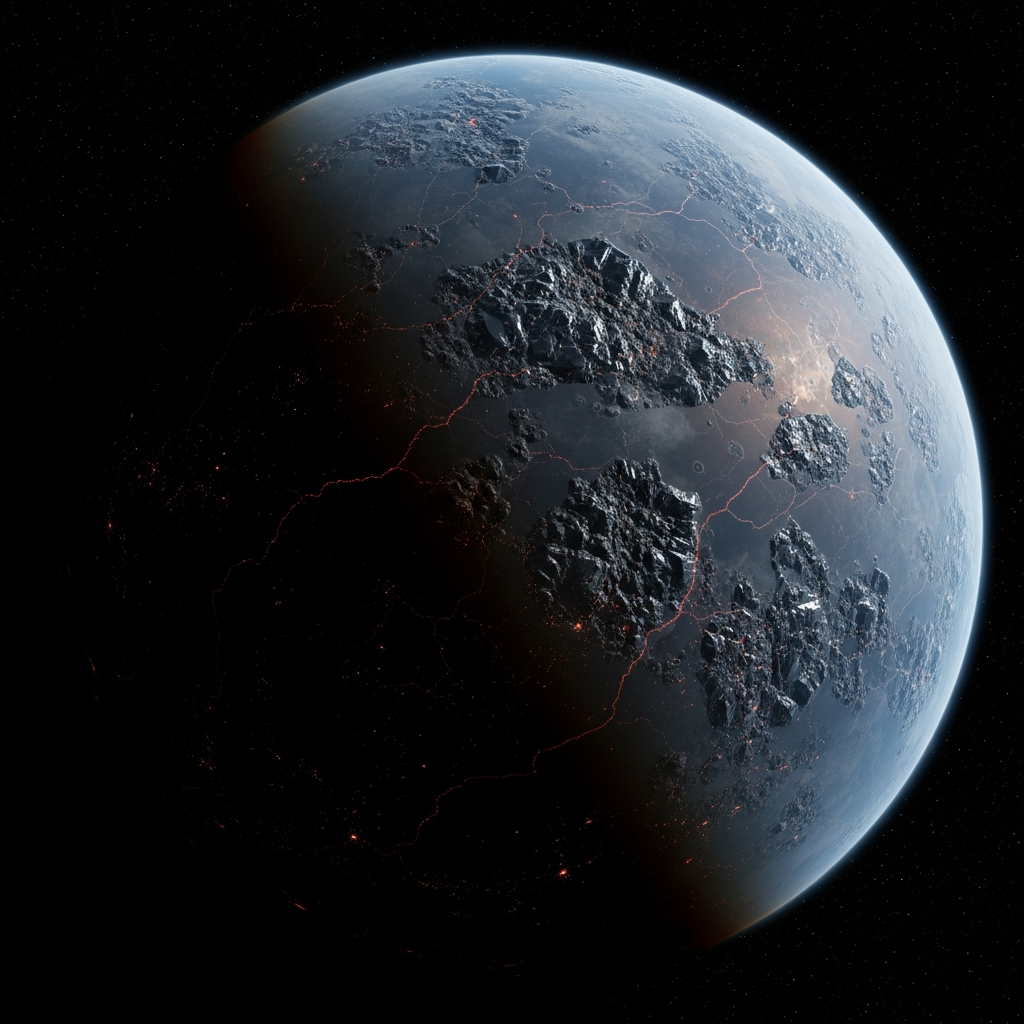

These planets are envisioned as solid worlds with surfaces rich in carbon compounds, potentially featuring graphite plains or diamond crusts. Their morphology may include volcanic activity involving carbon-based materials, creating landscapes unlike any silicate-based planet. The overall density is expected to be higher than typical rocky planets due to the presence of dense carbon allotropes.

While carbon planets remain theoretical with no confirmed examples, their unique chemistry could influence atmospheric composition and surface processes. Predicted atmospheres may be poor in water and oxygen but rich in carbon monoxide, methane, and other hydrocarbons. These planets, if discovered, would offer new insights into planetary formation and the diversity of planetary environments.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtPopularly dubbed "diamond planets," carbon planets have captured imagination in science fiction and speculative astronomy as exotic, glittering worlds. Though not formally recognized by major astronomical bodies, they feature in discussions about planetary diversity and the potential for unusual planetary types beyond our Solar System.

There are no empirical constraints on the orbits of carbon planets, as none have been confirmed. Theoretical models suggest they could form at a variety of distances from their stars, depending on the carbon-to-oxygen ratio in the protoplanetary disk and local disk chemistry.

Carbon planets are expected to have masses ranging roughly from half to ten times that of Earth and radii between 0.8 and 2 Earth radii. Their densities are predicted to be higher than typical rocky planets, around 3.5 to 5.5 grams per cubic centimeter, due to dense carbon allotropes like diamond and silicon carbide dominating their interiors.

These planets are theorized to possess atmospheres poor in water and oxygen but rich in carbon-based gases such as carbon monoxide, methane, and other hydrocarbons. Atmospheric compositions remain highly model-dependent and have not been empirically measured.

Carbon planets have not been directly observed or explored. Their concept arises from theoretical modeling and astrophysical studies beginning in the early 21st century. No space missions have targeted or confirmed carbon planets, and their detection remains a challenge due to current observational limitations.

The potential for life on carbon planets is uncertain and likely limited by their unusual chemistry. Their atmospheres lack water vapor and oxygen, key ingredients for Earth-like life, and their surfaces may be inhospitable due to exotic carbon volcanism and mineralogy. However, their study expands our understanding of possible planetary environments beyond traditional habitable zones.