Mesquite

Mesquite is a genus of hardy, nitrogen-fixing trees (Prosopis spp.) renowned for their drought tolerance, multipurpose pods, and ecological value in arid landscapes.

Mesquite is a genus of hardy, nitrogen-fixing trees (Prosopis spp.) renowned for their drought tolerance, multipurpose pods, and ecological value in arid landscapes.

Mesquite traces its roots to the genus Prosopis, with centers of diversity spanning the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Species such as Prosopis glandulosa (honey mesquite) are native to the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, while Prosopis juliflora originated in Central and South America but has been widely introduced to Africa, Asia, and Australia. Mesquite’s ancient lineage within the subfamily Caesalpinioideae of Fabaceae reflects its adaptation to challenging environments over millennia. Although most mesquite trees remain wild or naturalized, limited selection for improved pod yield or forage quality has occurred in research settings.

Mesquite belongs to the botanical family Fabaceae (Leguminosae), subfamily Caesalpinioideae (formerly Mimosoideae), and the genus Prosopis. This places it firmly within the legume family, known for podded fruits and nitrogen-fixing abilities. Notable species include Prosopis glandulosa, Prosopis juliflora, Prosopis pallida, and Prosopis velutina. Taxonomic synonyms such as Neltuma have been proposed, but Prosopis remains the accepted genus among leading authorities.

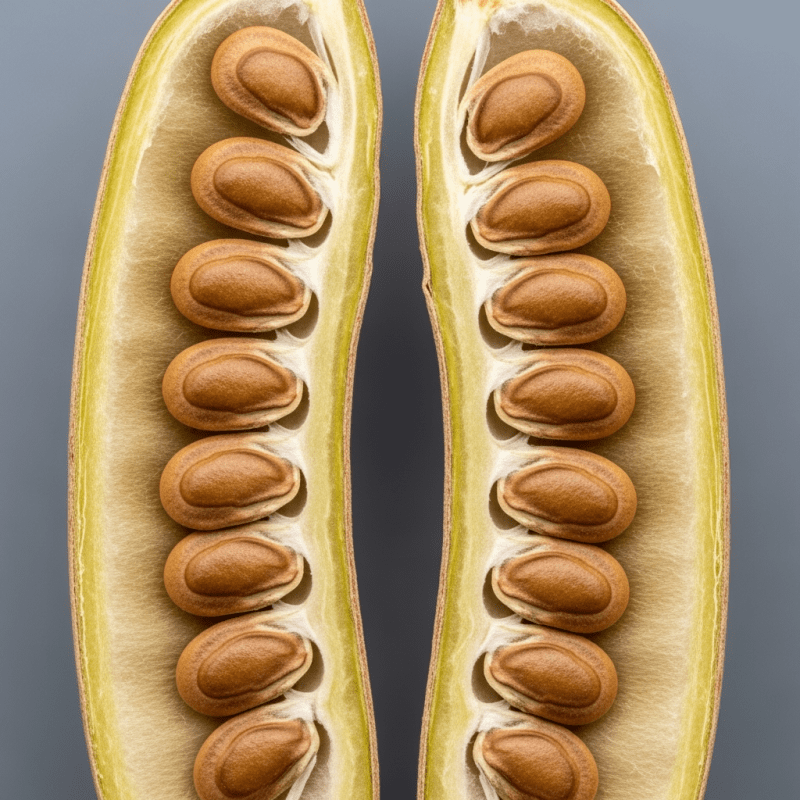

Mesquite trees are medium-sized, typically reaching heights of 3 to 15 meters. They feature a spreading canopy, rough fissured bark, and thorny branches. The leaves are bipinnate, lending a feathery texture, while the small, yellowish flowers cluster densely along spikes. Their most distinctive trait is the long, slender pod—measuring 10 to 30 centimeters—filled with hard seeds nestled in a sweet, starchy pulp. The deep taproot system is a hallmark of their drought resilience.

Mesquite’s versatility is evident in its many uses. The pods are ground into flour for baking, prized for their sweet, nutty flavor and low glycemic index. Livestock benefit from the high-protein pods and foliage as forage, especially in arid rangelands. The dense wood is sought after for barbecue and smoking, furniture, fence posts, and crafts. Mesquite trees also serve as windbreaks, shade providers, and ornamentals in landscaping. In some regions, honey is produced from their nectar, and industrial uses include gum extraction and potential biofuel production.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtMesquite holds a special place in the cultures of desert and grassland peoples. Indigenous communities in North and South America have long relied on mesquite pods for food and flour, integrating them into traditional diets and ceremonies. The wood’s aromatic qualities make it a staple in barbecue culture, especially in the southwestern United States. In Spanish-speaking regions, "algarrobo" is both a culinary and cultural reference, while in Africa and India, mesquite is woven into local agricultural and ecological narratives, sometimes as a symbol of resilience or, conversely, as a problematic invasive species.

Mesquite has a predominantly wild or naturalized history, with little formal domestication. While some research-based selection for improved pod yield and forage quality exists, there are no documented breeding programs or named cultivars. Its spread across continents is largely due to natural dispersal and human introduction for purposes such as land restoration, forage, and fuelwood. Mesquite’s ancient lineage within Fabaceae underscores its long-standing ecological role in arid and semi-arid regions.

Mesquite grows as a medium-sized tree with a deep taproot system, enabling survival in harsh, dry climates. It develops a spreading canopy, bipinnate leaves, and thorny branches. The lifecycle includes flowering—small yellowish blooms in dense spikes—followed by the production of long pods containing hard seeds. Mature trees can yield 20 to 100 kg of pods annually, depending on species and conditions. Mesquite’s resilience allows it to thrive in poor soils, high temperatures, and even periodic flooding.

Like many legumes, mesquite forms a symbiotic relationship with soil bacteria to fix atmospheric nitrogen. This process enriches the soil, improving fertility and supporting the recovery of degraded landscapes. Mesquite’s nitrogen-fixing ability makes it a valuable component in sustainable agriculture and land restoration, particularly in arid regions where soil nutrients are limited.

Mesquite pods are ground into a naturally sweet, nutty flour that features a low glycemic index, making it suitable for diabetic-friendly recipes and gluten-free baking. Traditional uses include breads, cakes, and porridges. While the seeds are generally too hard for direct consumption, the pods and foliage provide high-protein forage for livestock. Mesquite honey, derived from flower nectar, is a regional delicacy. The wood’s aromatic qualities make it prized for barbecue and smoking, imparting a distinctive flavor to grilled foods.

Mesquite flour and wood products occupy niche markets in North America, valued for specialty baking and barbecue. In other regions, mesquite’s primary commercial roles are as forage and fuelwood. Market value varies widely depending on product and geography. Regulatory codes for mesquite products are listed in FAO and USDA databases, though they are not standardized across all species. Industrial uses, such as gum extraction and potential biofuel production, add to mesquite’s economic diversity.

Mesquite is generally resilient to abiotic stresses like drought, high temperatures, and salinity, but it can be susceptible to certain fungal pathogens and insect pests. Bruchid beetles are known to infest seeds, affecting pod quality and viability. While mesquite’s hardiness makes it a reliable choice for challenging environments, periodic monitoring for pests and diseases is recommended, especially in cultivated or restored landscapes.

Mesquite encompasses several notable species and regional names. Prosopis glandulosa is commonly called "honey mesquite," while Prosopis velutina is "velvet mesquite." In Spanish-speaking regions, "algarrobo" refers to Prosopis pallida or P. juliflora. In India, P. juliflora is known as "vilayati babul" or "Siris," and in Kenya, it is called "Mathenge." Other aliases include "mesquite bean" for the pods and "Neltuma" as a proposed taxonomic synonym. Mesquite’s status as an invasive species in Australia and parts of Africa further shapes its regional identity and management practices.