Kudzu

Kudzu is a perennial climbing vine in the legume family, renowned for its rapid growth, nitrogen-fixing ability, and dual reputation as both a valuable resource and an invasive species.

Kudzu is a perennial climbing vine in the legume family, renowned for its rapid growth, nitrogen-fixing ability, and dual reputation as both a valuable resource and an invasive species.

Kudzu (Pueraria montana) originates from East Asia, specifically China, Japan, and Korea. Scientifically described in the early 19th century, it was named for Swiss botanist Marc Nicolas Puerari. Kudzu made its North American debut at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, later promoted for erosion control and forage, especially during the 1930s and 1940s by the U.S. Soil Conservation Service. Its spread outside Asia is largely due to these introductions, with wild and naturalized populations now common in the southeastern United States.

Kudzu belongs to the botanical family Fabaceae (legumes), genus Pueraria, and species montana. The most widespread variety is Pueraria montana var. lobata. As a legume, it shares the family’s hallmark traits: podded fruit and the capacity for nitrogen fixation, placing it among a diverse group that includes beans, peas, and lentils.

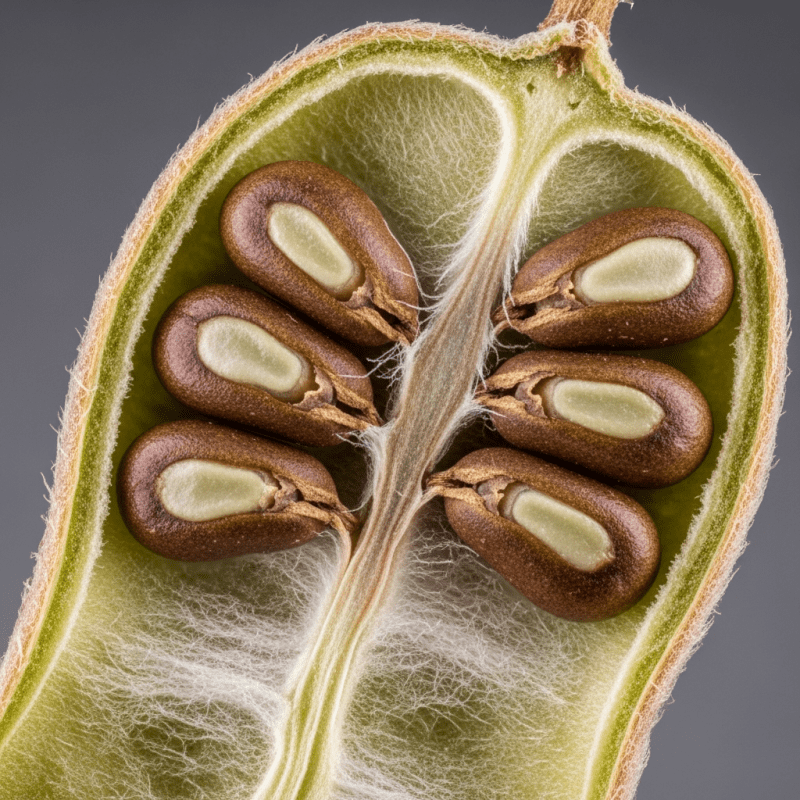

Kudzu is a vigorous, woody, deciduous vine with twining stems that can reach up to 30 meters in length and 20 centimeters in diameter. Its leaves are alternate, compound, and trifoliate—each leaflet ovate to broadly ovate, often lobed, and measuring up to 20 cm long. In late summer, kudzu produces fragrant, purple to reddish pea-like flowers arranged in axillary racemes. The fruit is a flattened, hairy legume pod containing hard seeds. Below ground, kudzu forms massive tuberous roots that can extend up to 2 meters.

Kudzu’s rapid vegetative spread enables it to cover vast areas, climbing over trees, shrubs, and structures. Its uses are multifaceted: it serves as forage for livestock, improves soil through nitrogen fixation, and is effective for erosion control due to its dense ground cover. In East Asia, its roots are harvested for starch used in traditional foods, while young shoots and leaves are edible. However, in regions where it is introduced, kudzu’s aggressive growth often leads to ecological disruption, earning it the label of an invasive species.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtKudzu holds a unique place in both Eastern and Western cultures. In Japan and China, it is valued for its culinary and medicinal uses—kudzu starch is prized for its purity in traditional dishes, and the root is used in herbal medicine. In the United States, kudzu has become a symbol of invasive species, often referenced in art, literature, and popular culture as the “vine that ate the South.” Its dual identity as both a resource and a problem reflects the complex relationship between humans and the plant.

Kudzu’s domestication is informal, with propagation primarily from wild and naturalized populations rather than selective breeding. Native to East Asia, it was introduced to the United States in the late 19th century for ornamental and practical purposes. Its use for erosion control and forage was heavily promoted in the early 20th century, but formal cultivar development is absent. Today, kudzu’s history is marked by its transition from valued import to invasive species in many regions.

Kudzu is a perennial, deciduous vine characterized by vigorous, climbing growth. Stems can extend up to 30 meters, twining over any available support. Leaves emerge in spring, followed by fragrant, pea-like flowers in late summer. The plant sets hairy legume pods containing hard seeds, but spreads most effectively via vegetative means—rooting at stem nodes and regenerating from root crowns. Kudzu’s lifecycle allows for rapid establishment and persistent regrowth, making control challenging where it is unwanted.

Like other legumes, kudzu forms a symbiotic relationship with rhizobia bacteria in its roots, enabling it to fix atmospheric nitrogen. This process enriches soil fertility, supports plant growth, and benefits subsequent crops in rotation. Kudzu’s dense ground cover also helps prevent erosion, making it useful for land reclamation and soil improvement, especially in degraded or sloped areas.

In East Asia, kudzu roots are harvested for their starch, known as kuzuko, which is used in noodles, jellies, and desserts prized for their texture and purity. Young leaves, shoots, and flowers are edible as vegetables or herbal teas. Kudzu forage is high in protein and palatable to livestock. The roots are rich in carbohydrates, while the plant is also used in traditional medicine for various ailments. Outside Asia, culinary use is limited due to its invasive reputation.

Kudzu’s commercial cultivation is rare outside its native range, with limited market value due to its invasive status. In East Asia, products made from kudzu starch are valued, but formal trade infrastructure is minimal elsewhere. In the United States, kudzu is not widely traded, and its movement is restricted in many states. The USDA PLANTS Database symbol for kudzu is PUMO; FAO trade codes are not standardized for this species.

Kudzu is notably resistant to most pests and diseases, contributing to its aggressive spread in new environments. While its robust growth protects it from many threats, this same trait allows it to suppress native plant communities and disrupt local ecosystems. Its regenerative capacity from root crowns and stem fragments makes management and control difficult, especially in regions where it is invasive.

Kudzu is known by several scientific synonyms, including Pueraria lobata and Pueraria thunbergiana. Regional names reflect its broad distribution: "kuzu" in Japan, "gé gēn" in China, and "kudzu vine" in English. In the southeastern United States, it is simply called "kudzu." The most common variety is Pueraria montana var. lobata, widely referenced in both agricultural and invasive species literature.