Indigo

Indigo is a group of leguminous plants in the genus Indigofera, globally renowned as the primary natural source of blue indigo dye for textiles and art.

Indigo is a group of leguminous plants in the genus Indigofera, globally renowned as the primary natural source of blue indigo dye for textiles and art.

The story of indigo begins in the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Indigofera tinctoria originated in India and Southeast Asia, while Indigofera suffruticosa is native to Central and South America. Indigo dye extraction dates back at least 6,000 years, with ancient civilizations in India, Egypt, China, and the Americas cultivating these plants for their vibrant pigment. The domestication of indigo species predates modern breeding, and no single breeder or institution is credited with their development; instead, their spread is a testament to human ingenuity and global exchange.

Indigo belongs to the family Fabaceae (Leguminosae), a diverse group of legumes. Within this family, it is classified under the genus Indigofera, which encompasses over 750 species. The most notable dye-producing species are Indigofera tinctoria and Indigofera suffruticosa. As legumes, indigo plants share the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, contributing to soil health and agricultural sustainability.

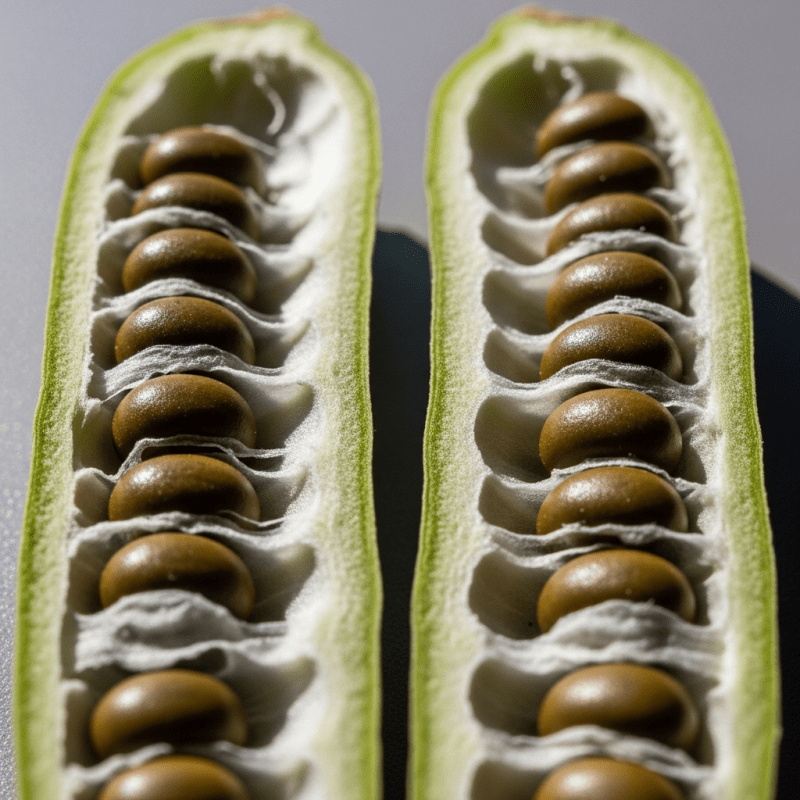

Indigo plants are typically perennial or annual shrubs, ranging from 0.5 to 2 meters in height. Their leaves are pinnate, composed of 5 to 13 delicate leaflets, and their small flowers—pink to violet—cluster along slender racemes. After flowering, the plants produce cylindrical seed pods filled with several small seeds. The overall form is airy and bushy, with a subtle beauty that belies their transformative power as dye plants.

The primary function of indigo is the extraction of natural blue dye from its leaves, a process involving fermentation and precipitation. Indigo dye has colored textiles for millennia, prized for its rich hue and lasting quality. Beyond dye production, some Indigofera species are used as green manure, cover crops, and forage, thanks to their nitrogen-fixing abilities. However, indigo is not edible and may be mildly toxic if ingested, so its interaction with humans is almost entirely through craft, agriculture, and environmental stewardship.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtIndigo holds a storied place in human culture, symbolizing royalty, spirituality, and artistry across continents. In India, indigo dye was central to ancient textile traditions and trade, while in West Africa, it remains integral to ceremonial garments and artistic expression. The plant's pigment shaped the global textile industry, especially during the colonial era, and continues to inspire artisans and designers seeking natural, sustainable colors. Indigo's legacy is woven into the fabric of history, from ancient murals to modern denim.

Indigo's domestication predates recorded history, with evidence of cultivation and dye extraction in ancient India, Egypt, China, and the Americas as early as 4000 BCE. The plants were selected and grown for their pigment content long before formal breeding programs existed. Over centuries, indigo spread along trade routes, becoming a cornerstone of textile economies and colonial commerce. No specific wild progenitor or cultivar lineage is documented, as the use of indigo is rooted in traditional practices and local adaptation rather than scientific breeding.

Indigo plants grow as annual or perennial shrubs, typically reaching heights of 0.5 to 2 meters. They feature pinnate leaves, small pink to violet flowers, and slender seed pods. The plants are drought-tolerant and thrive in well-drained soils, maturing rapidly in warm climates. After flowering and seed set, leaves are harvested for dye extraction, with processing required soon after harvest to preserve pigment precursors. Indigo's lifecycle supports both agricultural production and soil enrichment.

Like all legumes, indigo forms a symbiotic relationship with soil bacteria, enabling it to fix atmospheric nitrogen. This process enriches the soil, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers and supporting sustainable crop rotations. Indigo is often used as a green manure or cover crop, improving soil structure and fertility for subsequent plantings.

Indigo has no significant culinary uses, as its plant parts are not edible and may be mildly toxic if consumed. Unlike many other legumes, indigo is valued exclusively for its dye properties and agricultural benefits, not for nutrition or food preparation.

Indigo dye was once a major commodity in global trade, especially during the colonial era when it fueled textile industries across Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Today, natural indigo remains important for artisanal and organic textile production, prized for its unique hue and eco-friendly profile. The principal trade code for indigo dye is HS Code 3201.20. While the plant itself is not widely traded, its dye and agricultural uses continue to support local economies in regions where Indigofera species are cultivated.

Indigo plants generally exhibit good resistance to pests but can be susceptible to root rot and fungal diseases, particularly in poorly drained soils. Their drought tolerance makes them resilient in challenging environments, but careful management of soil moisture is essential to prevent disease outbreaks and ensure healthy growth.

Key indigo species include Indigofera tinctoria ("true indigo," "Indian indigo") and Indigofera suffruticosa ("Guatemalan indigo," "West Indian indigo," "wild indigo"). Regional cultivation spans Africa, Asia, and the Americas, with local names such as "nila" (Hindi), "añil" (Spanish), and "neel" (Bengali). Taxonomic synonyms include Indigofera arrecta and Indigofera coerulea. Note that "woad" refers to a different, non-legume dye plant (Isatis tinctoria), sometimes confused with indigo in trade literature.