Clover

Clover is a group of herbaceous plants in the genus Trifolium, celebrated for their trifoliate leaves and vital role in agriculture as forage crops and natural soil improvers.

Clover is a group of herbaceous plants in the genus Trifolium, celebrated for their trifoliate leaves and vital role in agriculture as forage crops and natural soil improvers.

Clover’s story begins in the temperate regions of Europe, Asia, North Africa, and North America, where its wild ancestors thrived in meadows and grasslands. Over centuries, distinct species such as red clover (Trifolium pratense), white clover (Trifolium repens), and subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum) were domesticated and adapted for agricultural use. Modern cultivars have roots in international breeding programs, with notable varieties like 'Ladino' tracing back to Italy in the early 20th century and 'Kenland' released by the University of Kentucky in 1954.

Clover belongs to the botanical family Fabaceae (Leguminosae), within the genus Trifolium. This places it among the legumes—a group renowned for their podded fruits and nitrogen-fixing abilities. With over 250 species, clover is classified as a forage legume, distinct from food legumes like beans and peas. Scientific naming follows binomial nomenclature, such as Trifolium pratense for red clover.

Clover plants are easily recognized by their three-part leaves, which sometimes present a rare four-leaf variant. Their stature varies: red clover grows upright to 30–80 cm, white clover forms low, creeping mats just 5–20 cm tall, and subterranean clover creates dense, ground-hugging carpets. Flowers cluster in small, rounded heads, displaying hues from white and pink to vivid red and purple, often dotting pastures and lawns with cheerful color.

Clover’s primary function is as a forage crop for livestock, providing nutritious grazing and hay. It is also widely used as a cover crop and green manure, enriching soils and preventing erosion. Through symbiosis with Rhizobium bacteria, clover fixes atmospheric nitrogen, naturally fertilizing fields. Beyond agriculture, clover flowers support honeybee populations, contributing to the production of clover honey—a valued commercial product. In some cultures, clover is used in herbal remedies and, occasionally, as a salad green or tea.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtClover holds a special place in folklore and symbolism. The four-leaf clover is a universal emblem of luck, while the three-leaf form is associated with Irish heritage and the shamrock. Its presence in meadows and lawns has inspired poetry, art, and national icons. Clover honey is prized in culinary traditions, and red clover features in herbal medicine, valued for its isoflavones. Across continents, clover’s resilience and abundance have made it a symbol of prosperity and renewal.

Clovers have been cultivated for centuries, with major species originating in Europe, Asia, North Africa, and the Mediterranean. Early domestication focused on their value as forage and soil enhancers. Modern breeding, led by institutions like USDA and FAO, has produced numerous cultivars tailored to diverse climates and agricultural needs. Notable pedigrees include 'Ladino' white clover from Italy and 'Kenland' red clover from Kentucky, reflecting the global spread and adaptation of clover species.

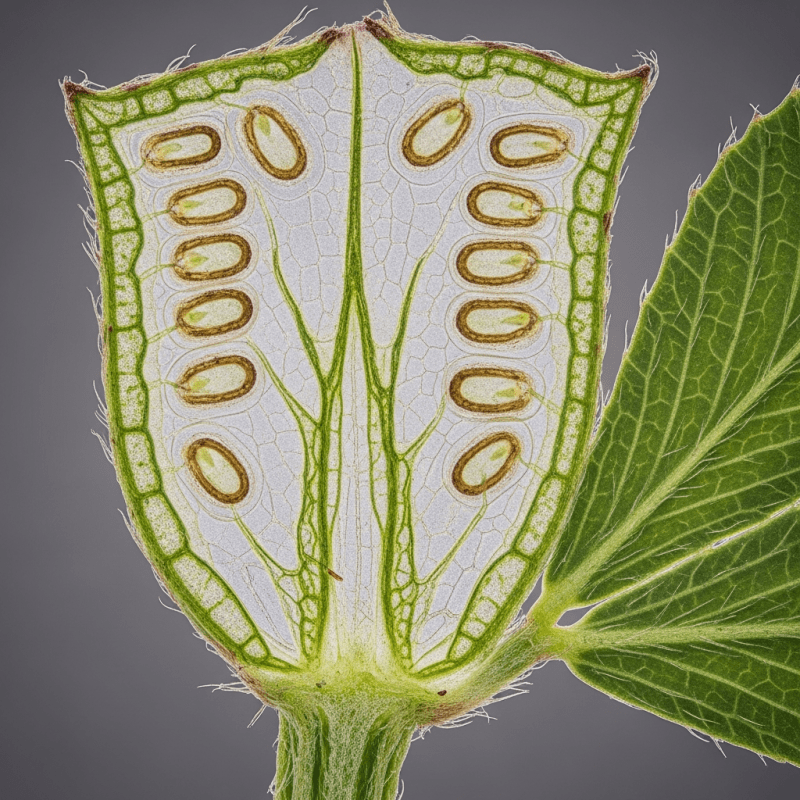

Clover species exhibit varied growth habits: red clover is upright and short-lived (2–3 years), white clover is prostrate and perennial (up to 5 years), and subterranean clover is annual and mat-forming. All feature trifoliate leaves and small, clustered flowers. Lifecycles range from annual reseeding (subterranean clover) to persistent perennial swards (white clover). Under optimal conditions, red clover yields 5–10 tons of dry matter per hectare annually, while white clover persists longer but with lower yield.

As legumes, clovers form symbiotic relationships with Rhizobium bacteria in their root nodules, enabling them to fix atmospheric nitrogen. This process naturally enriches soils, reduces the need for synthetic fertilizers, and supports sustainable crop rotations. Clover cover crops help prevent erosion, improve soil structure, and boost overall field productivity, making them indispensable in regenerative agriculture.

Clover’s main culinary contribution is indirect—its flowers support the production of clover honey, a delicacy in many regions. Red clover is used in herbal medicine and as a source of isoflavones (phytoestrogens). Occasionally, young leaves and flowers are added to salads or brewed as tea. As forage, clover is rich in protein, enhancing livestock nutrition and productivity.

Clover’s commercial value centers on livestock productivity, soil health, and honey production. Subterranean clover dominates Australian pasture systems, while berseem (Egyptian clover) is vital in Egypt and South Asia. Ornamental uses in lawns and wildflower mixes add to its market presence. International trade recognizes clover species with FAO codes: TRFPRT (red clover), TRFREP (white clover), and TRFSUB (subterranean clover).

Clovers face challenges from diseases such as clover rot (Sclerotinia trifoliorum) and root nematodes. Resistance varies by species and cultivar, with some types showing improved tolerance to drought and cold. Proper management and breeding have enhanced resilience, but ongoing vigilance is needed to maintain healthy stands, especially in intensive pasture systems.

Regional adaptation is notable: subterranean clover is dominant in Australian pastures, while berseem is widely grown in Egypt and South Asia.