Bambara groundnut

Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) is a drought-tolerant African legume prized for its underground pods, nutritional richness, and resilience in marginal soils.

Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) is a drought-tolerant African legume prized for its underground pods, nutritional richness, and resilience in marginal soils.

Bambara groundnut traces its origins to West Africa, particularly Nigeria, Ghana, and Cameroon, where it has been cultivated for centuries. Its domestication is rooted in traditional smallholder farming, with local landraces passed down through generations. While the exact timeline remains unclear, archaeobotanical evidence confirms its longstanding role as a staple crop in semi-arid regions. Modern breeding efforts, led by organizations such as the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, aim to enhance its yield and stress tolerance, but most production still relies on locally adapted varieties.

Bambara groundnut belongs to the botanical family Fabaceae (Leguminosae), subfamily Faboideae, and genus Vigna. Its accepted scientific name is Vigna subterranea, though it was previously known as Voandzeia subterranea. As a legume, it shares the family’s hallmark traits: podded fruit and the capacity for nitrogen fixation, placing it alongside beans, peas, and lentils within the broader legume taxonomy.

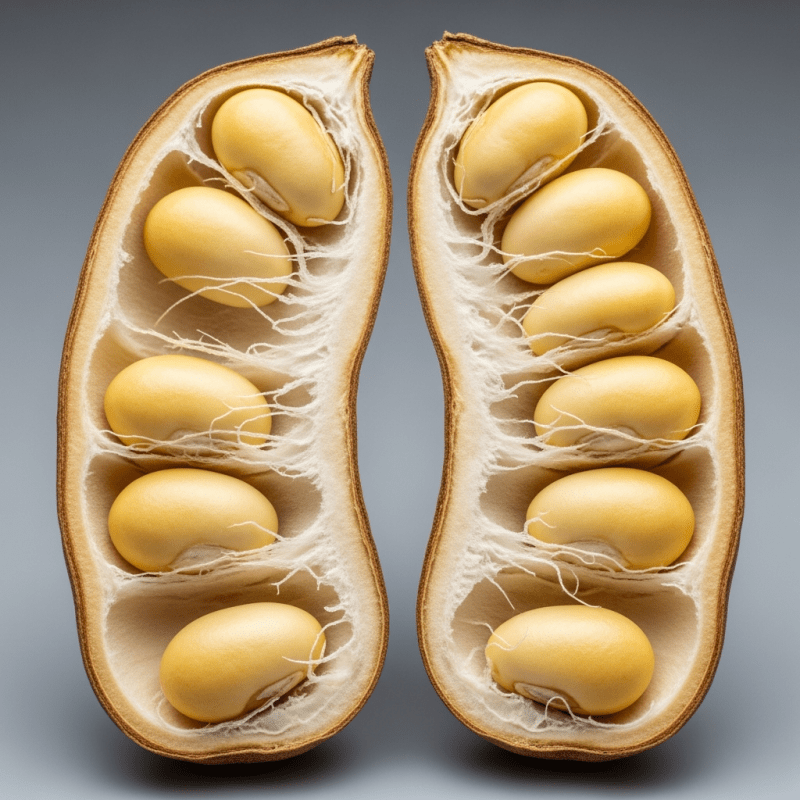

The plant is an annual herb with trifoliate leaves and a prostrate to semi-erect growth habit. Its flowers range from yellow to purple, adding subtle color to the field. Bambara groundnut’s most distinctive trait is geocarpy: after pollination, its pods develop and mature underground. The pods are small (1.5–2.5 cm), each containing one or two seeds. Seeds themselves are globular to oval, and their color palette spans cream, red, brown, black, and mottled patterns, reflecting the diversity of local varieties.

Bambara groundnut thrives in poor, sandy soils and requires minimal inputs, making it ideal for low-resource farming. Its drought tolerance and underground pod formation allow it to flourish where other crops struggle. The seeds are consumed boiled, roasted, or ground into flour, and feature in traditional dishes such as Nigeria’s “okpa.” Beyond human food, the crop is also used as animal feed and plays a vital role in crop rotations, enriching soils through nitrogen fixation.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtAcross Africa, Bambara groundnut holds cultural importance as a symbol of resilience and nourishment. Its presence in traditional dishes—like “okpa” in Nigeria and “toh” in Burkina Faso—reflects its deep culinary heritage. The crop’s adaptability and nutritional value have made it a staple in communities facing challenging climates, and its many local names speak to its embeddedness in regional identity and language.

Bambara groundnut’s domestication is deeply intertwined with West African agricultural traditions. Archaeobotanical records suggest its cultivation spans several centuries, but the precise origins and timeline remain elusive due to its landrace nature and lack of formal breeding history. Propagated mainly by smallholder farmers, the crop spread across the continent through local adaptation and exchange. Modern research institutions now work to improve its agronomic traits, but its genetic diversity is still largely maintained through traditional practices.

This annual legume exhibits a prostrate or semi-erect growth form, with trifoliate leaves and vibrant flowers. After flowering, fertilized ovules are pushed underground, where pods develop and mature—a process unique among legumes. The lifecycle from planting to harvest ranges from 90 to 150 days, depending on the variety and environmental conditions. Bambara groundnut’s robust nature allows it to complete its lifecycle with minimal water and fertilizer, maturing reliably even in marginal soils.

Like other legumes, Bambara groundnut forms a symbiotic relationship with soil bacteria to fix atmospheric nitrogen. This natural process enriches the soil, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers and supporting sustainable agriculture. Its ability to thrive in poor soils and contribute to soil fertility makes it especially valuable in crop rotations and intercropping systems, benefiting both farmers and the environment.

Bambara groundnut seeds are versatile in the kitchen: they are boiled, roasted, or ground into flour for baking and thickening soups. Signature dishes include “okpa” in Nigeria and “toh” in Burkina Faso. The seeds are notably nutritious, containing 16–24% protein, 50–65% carbohydrates, and moderate fat, making them a vital source of plant-based nutrition in regions with limited access to animal protein. The flour is also used in gluten-free baking and as a protein-rich ingredient in traditional recipes.

Bambara groundnut is primarily grown for subsistence by smallholder farmers in Africa, but local and regional markets trade both raw and processed seeds. Its commercial cultivation is limited outside Africa, though interest is rising in Asia and Europe due to its climate resilience. The crop is registered under FAO commodity code 0197 and USDA PLANTS symbol VIGS2, reflecting its recognized status in agricultural trade, even if global volumes remain modest.

Bambara groundnut is generally robust against pests and diseases, a trait that supports its low-input cultivation. However, it can be affected by fungal pathogens such as Fusarium species and viral infections, particularly in humid conditions. Its hard seed coat offers natural protection against storage insects, helping preserve seed quality during post-harvest storage. Overall, the crop’s resilience contributes to its reliability in challenging environments.

Bambara groundnut is known by a rich array of regional names: “nyimo bean” in Zimbabwe, “jugo bean” in South Africa, “okpa” in Nigeria, “tiga” in Mali, “kunga” in Ghana, and “pois bambara” in Francophone Africa. Scientific synonyms include Voandzeia subterranea. Most production comes from heterogeneous landraces, with no widely recognized formal cultivars, reflecting its deep local adaptation and cultural diversity across Africa.