Atlantic Sturgeon

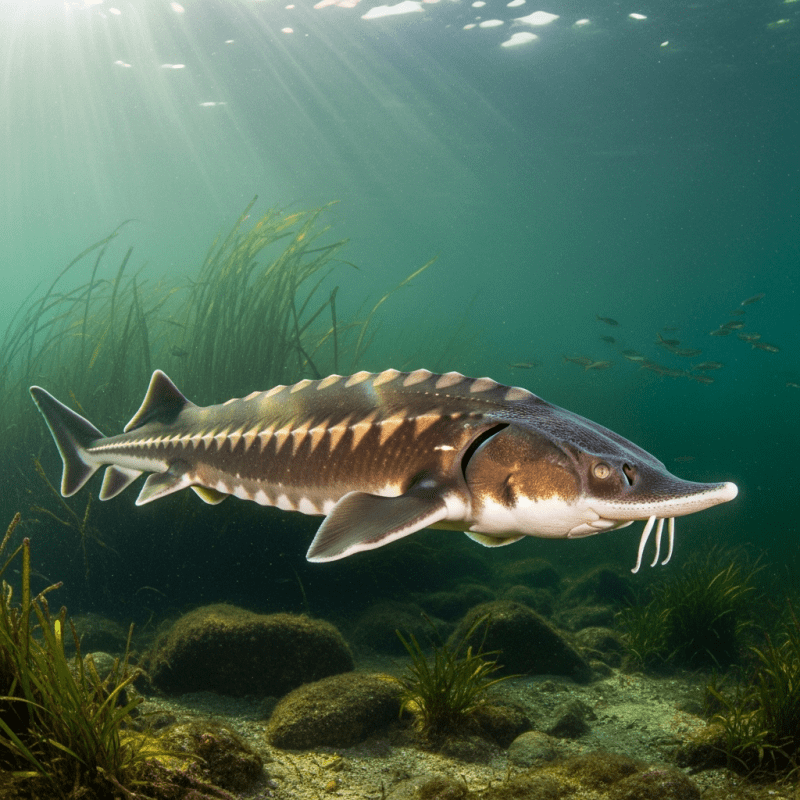

The Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) is a large, long-lived anadromous fish known for its armored body and elongated snout, native to the Atlantic coast of North America and parts of Europe.

The Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) is a large, long-lived anadromous fish known for its armored body and elongated snout, native to the Atlantic coast of North America and parts of Europe.

First described by William Mitchill in 1815, the Atlantic Sturgeon belongs to one of the most ancient families of ray-finned fishes, Acipenseridae, with origins tracing back to the Cretaceous period. While naturally native to the Atlantic coasts of North America and Europe, the Baltic population was introduced from North America in the 19th century following the extinction of the native European sturgeon.

The Atlantic Sturgeon is classified within the family Acipenseridae, genus Acipenser, and species oxyrinchus. This family comprises some of the oldest surviving ray-finned fishes, characterized by their cartilaginous skeletons and bony scutes.

This species features an elongated, torpedo-shaped body armored with five rows of bony scutes. Its coloration ranges from olive-brown to bluish-black on the back, fading to a pale underside. A long, pointed snout equipped with four sensory barbels enhances its ability to detect prey in murky waters. Adults typically measure between 1.8 and 4.2 meters in length and can weigh up to 360 kilograms.

The Atlantic Sturgeon is an anadromous fish, spending much of its life in marine environments before migrating into freshwater rivers to spawn. It is slow-growing and late to mature, reaching sexual maturity between 10 and 20 years of age. Historically, humans have valued it primarily for its roe, which is processed into prized caviar, while its flesh is consumed fresh, smoked, or pickled. Its interactions with humans today are tightly regulated to protect dwindling populations.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtThe Atlantic Sturgeon holds considerable cultural importance, especially among indigenous peoples and colonial communities along the Atlantic coast. It has been a symbol of abundance and a key resource in local culinary traditions. The species’ roe, transformed into caviar, has long been a luxury delicacy, contributing to its historical economic and cultural value.

The Atlantic Sturgeon occupies both marine and freshwater habitats, reflecting its anadromous lifestyle. It ranges along the Atlantic coast of North America, from Canada to the southeastern United States, and has a transplanted population in the Baltic Sea. It migrates upstream into freshwater rivers such as the Chesapeake Bay, Hudson River, and Delaware River to spawn.

The Atlantic Sturgeon feeds primarily on benthic organisms, using its sensitive barbels to detect prey on river and ocean floors. Its diet includes small fish, crustaceans, and invertebrates, which it consumes by suction feeding along the substrate.

Atlantic Sturgeon reproduce by migrating from saltwater to freshwater rivers where spawning occurs. They reach sexual maturity late, between 10 and 20 years of age, and are slow to grow. Spawning typically takes place in large, free-flowing rivers with clean gravel beds, essential for egg survival and development.

While wild Atlantic Sturgeon populations are not managed for commercial yield due to conservation concerns, aquaculture efforts exist primarily to produce caviar. These farming operations focus on slow-growing stocks and employ controlled breeding methods to sustain production without impacting wild stocks. Commercial fishing is strictly regulated or prohibited in many regions to protect the species.

The Atlantic Sturgeon is listed as threatened or endangered across much of its range, facing threats from overfishing, habitat degradation, pollution, and migration barriers such as dams. Conservation measures include habitat restoration, fishing restrictions, and international trade controls under CITES Appendix II. Despite protections, populations remain vulnerable and require ongoing efforts to ensure recovery.