Oviraptor

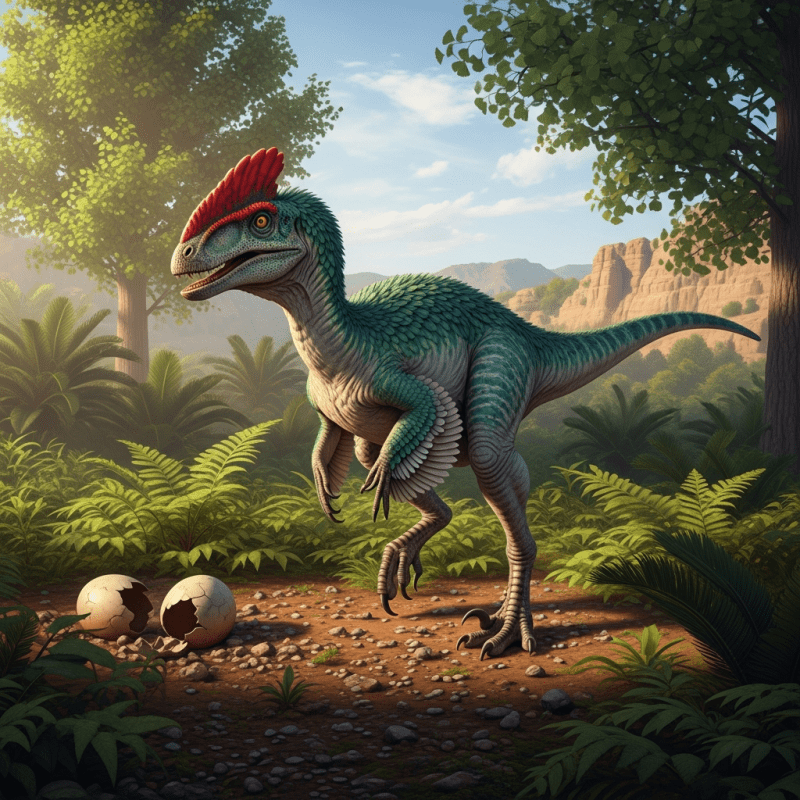

Oviraptor is a small, feathered theropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia, instantly recognizable for its beaked jaws, crest, and the once-misunderstood reputation as an "egg thief."

Oviraptor is a small, feathered theropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia, instantly recognizable for its beaked jaws, crest, and the once-misunderstood reputation as an "egg thief."

Oviraptor was first described in 1924 by paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, following its discovery in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia during the American Museum of Natural History’s Central Asiatic Expeditions. The holotype specimen (AMNH 6517) was famously found atop a nest of eggs in the Djadokhta Formation, leading to early speculation about its behavior. Later research revealed that these eggs likely belonged to Oviraptor itself, suggesting nurturing, brooding habits rather than predation.

Oviraptor belongs to the clade Oviraptorosauria within the order Theropoda, suborder Coelurosauria, and family Oviraptoridae. As a member of Dinosauria, it is part of the broader group of terrestrial vertebrates that dominated the Mesozoic Era. Its evolutionary placement highlights bird-like traits and close relationships with other feathered dinosaurs.

Oviraptor was a compact, bipedal dinosaur measuring about 1.5–2 meters in length and weighing 20–33 kg. Its most distinctive features include a short, deep, toothless beak, a prominent cranial crest, and evidence of feathers. The hands featured three curved claws adapted for grasping, while its tail was relatively short. These anatomical traits gave Oviraptor a bird-like silhouette, blending reptilian and avian characteristics.

Oviraptor’s behavior is best known for its inferred brooding habits, as fossil evidence suggests adults may have incubated their own eggs. Its skeletal adaptations—such as grasping hands—point to dexterous manipulation of objects, possibly eggs or small prey. While once thought to be an egg predator, modern interpretations favor a more nuanced view of its omnivorous or carnivorous diet and nurturing reproductive behavior. Oviraptor holds no direct utility for humans beyond its scientific and educational value.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtOviraptor has become emblematic in paleontology, museum displays, and educational media, often depicted as the classic "egg thief"—a myth now debunked by further research. Its story is a touchstone for how scientific understanding evolves, and it remains a popular figure in books, documentaries, and exhibitions that explore dinosaur reproduction and the origins of bird-like traits.

Oviraptor lived during the Late Cretaceous period, a time when dinosaurs flourished across diverse environments approximately 100–66 million years ago.

The first Oviraptor fossil was uncovered in 1923 in the Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, with the holotype specimen (AMNH 6517) famously found atop a nest of eggs. Subsequent discoveries have reinforced its role in studies of dinosaur reproduction and brooding behavior, though all confirmed fossils remain exclusive to this region.

Oviraptor inhabited the arid, sandy environments of the Djadokhta Formation in the Gobi Desert, Mongolia. Its distribution appears limited to this region, suggesting a specialized adaptation to local conditions during the Late Cretaceous.

Oviraptor’s diet is debated, but evidence points to omnivorous or carnivorous habits. Its beaked jaws and grasping hands suggest it could have consumed eggs, mollusks, small vertebrates, and possibly plant material, reflecting a flexible approach to feeding within its environment.

Details of Oviraptor’s growth and life cycle remain uncertain due to limited fossil specimens. However, its brooding behavior implies some degree of parental care, and its bird-like traits suggest developmental stages similar to those of modern avians. Lifespan and growth rates are not well constrained.

Like all non-avian dinosaurs, Oviraptor disappeared at the end of the Cretaceous, likely due to catastrophic events such as asteroid impact and volcanic activity that radically altered global ecosystems and climate.

Oviraptor is pivotal in paleontology for illuminating the evolution of reproductive behavior and bird-like traits among dinosaurs. Its fossils have helped overturn misconceptions and advanced the understanding of the link between non-avian dinosaurs and birds, making it a cornerstone genus in evolutionary studies.