True Sago Palm

The True Sago Palm (Metroxylon sagu) is a towering, tropical palm native to Southeast Asia, renowned as the world’s primary source of commercial sago starch.

The True Sago Palm (Metroxylon sagu) is a towering, tropical palm native to Southeast Asia, renowned as the world’s primary source of commercial sago starch.

Formally described in 1783 by Christen Friis Rottbøll, the True Sago Palm originates from the lowland swamp forests of Malaysia, Indonesia (Sumatra, Borneo, Papua), Brunei, and Papua New Guinea. It has flourished for centuries in these waterlogged habitats, where wild populations and extensive cultivation have shaped local economies and diets. Unlike many palms, Metroxylon sagu has no known cultivars or breeder lineage; its domestication centers on wild stands and traditional propagation, supporting rural communities across the region.

Metroxylon sagu belongs to the family Arecaceae, the true palm family. It is a monocotyledonous flowering plant, distinct from cycads and other palm-like species. Its genus, Metroxylon, is recognized for monocarpic palms that flower once before dying. This species is often confused with the unrelated cycad ‘sago palm’ (Cycas revoluta), but only Metroxylon sagu is a true palm and a commercial source of edible sago starch.

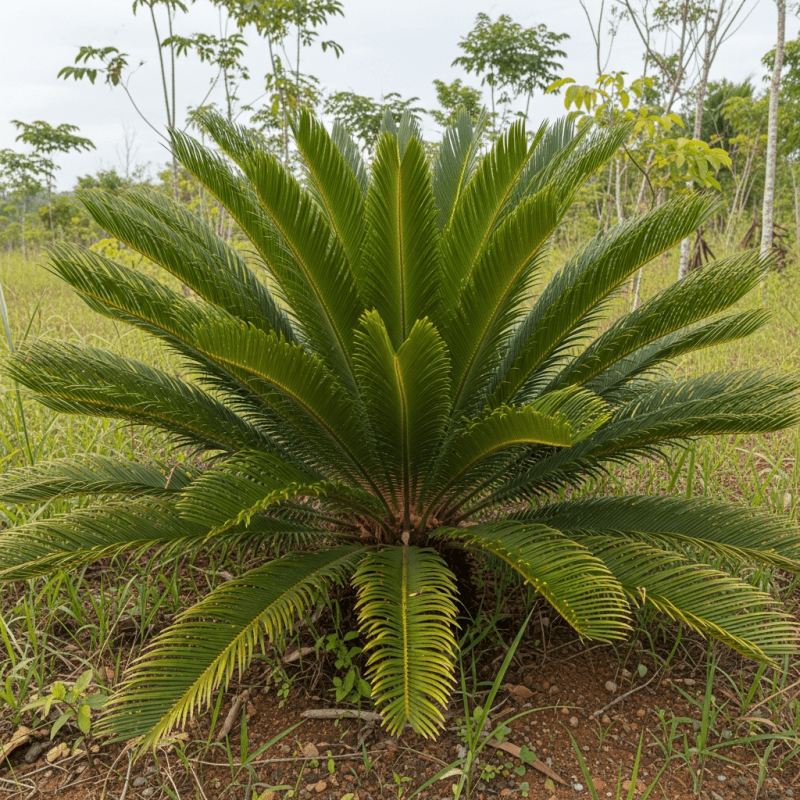

The True Sago Palm is a robust, spiny giant, typically reaching 10–15 meters in height with a trunk diameter of 30–60 cm. Its trunk is armored with persistent leaf bases and sharp spines, giving it a formidable appearance. The crown boasts feathery, pinnate leaves up to 7 meters long, each lined with numerous slender leaflets. At maturity, the palm produces a spectacular inflorescence up to 9 meters long, followed by clusters of globose, scaly drupes 2–4 cm in diameter. The overall look is both architectural and wild, suited to swampy, tropical landscapes.

Metroxylon sagu is monocarpic: it grows for 7–15 years, flowers once, then dies. Its main utility is the starchy pith within its trunk, which is harvested and processed into sago—a vital food staple in Southeast Asia and Melanesia. The palm is also used for construction materials (thatch, temporary shelters), animal fodder, fuel, and handicrafts. Propagation is typically by offshoots, as seeds are slow to germinate. Its resilience in flooded, peaty soils makes it ideal for wetland agriculture and ecological restoration.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtThe True Sago Palm is deeply woven into the fabric of Southeast Asian and Melanesian life. Sago starch underpins traditional diets, appearing in iconic dishes like sago pudding and papeda. The palm supports rural economies, providing both food security and employment. Its identity is sometimes muddled in popular culture, as the term ‘sago palm’ is also used for toxic cycads, but Metroxylon sagu remains the authentic, edible source celebrated in local customs and ceremonies.

Metroxylon sagu is the principal species cultivated for sago starch, but the genus Metroxylon includes several related palms adapted to wetland environments. Within the broader palm family (Arecaceae), there are over 180 genera and approximately 2,600 species, ranging from the coconut (Cocos nucifera) to the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera). However, Metroxylon sagu stands alone as the only true palm widely used for commercial sago production.

The True Sago Palm is native to tropical, lowland swamp forests across Southeast Asia—especially Malaysia, Indonesia (Sumatra, Borneo, Papua), Brunei, and Papua New Guinea. It thrives in waterlogged, peaty soils and tolerates seasonal flooding, making it a keystone species in wetland ecosystems. Its cultivation has expanded wherever such conditions exist, supporting both wild and managed populations throughout the region.

Metroxylon sagu prefers tropical climates and saturated, acidic soils. For successful cultivation, plant offshoots in waterlogged or peaty ground with ample sunlight. The palm requires minimal maintenance once established, but periodic monitoring for trunk rot and fungal pathogens is advised. Harvest occurs when the palm reaches maturity (7–15 years), just before flowering, to maximize starch yield. Seed propagation is possible but slow; vegetative propagation via suckers is far more efficient.

The True Sago Palm is economically vital in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, where sago starch extraction supports thousands of rural households. Sago is processed into flour, pearls, and cakes for local consumption and export. Industrial uses include starch for paper and textile production. The palm’s versatility extends to construction materials, animal feed, and handicrafts, making it a linchpin of wetland economies and food security.

Metroxylon sagu plays a crucial ecological role in wetland environments, stabilizing soils and supporting biodiversity. Its tolerance for flooding and poor soils enables sustainable agriculture in otherwise marginal lands. Sago palm cultivation can help preserve peatlands and reduce pressure on upland forests, though expansion must be managed to avoid habitat loss and waterway disruption. Overall, it is considered environmentally beneficial when grown in its native range and traditional systems.

The most common threats to Metroxylon sagu are trunk rot and fungal pathogens, especially in poorly drained or overcrowded stands. Good water management, crop rotation, and removal of infected material help maintain palm health. The species is generally resilient in its native habitat, but vigilance is needed to prevent outbreaks that can reduce starch yield and palm longevity.

The starchy pith of Metroxylon sagu’s trunk is its most valuable edible part, processed into sago flour, pearls, and cakes. Leaves and trunk bases are used for thatch, temporary structures, and fuel. The palm also provides animal fodder and raw material for handicrafts, making nearly every part of the plant useful in local economies.

Metroxylon sagu is not currently listed as threatened and remains abundant in its native range, thanks to both wild and cultivated populations. However, wetland habitat loss, unsustainable harvesting, and disease outbreaks pose localized risks. Conservation efforts focus on sustainable management of peatlands and traditional cultivation practices to ensure long-term viability of sago palm resources.