Oil Palm

The Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis) is a towering tropical palm renowned as the world’s leading source of commercial palm oil, powering global industries from food to cosmetics and biofuels.

The Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis) is a towering tropical palm renowned as the world’s leading source of commercial palm oil, powering global industries from food to cosmetics and biofuels.

Native to the lush rainforests of West and Central Africa, the oil palm has been cultivated for centuries by local communities. Its scientific description dates to 1763, credited to Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin. The species’ journey from African forests to global prominence began in the late 19th century, when seeds and germplasm were introduced to Southeast Asia, sparking the rise of vast plantations in Malaysia and Indonesia. Today, improved cultivars and hybrids—sometimes crossed with the American oil palm (Elaeis oleifera)—reflect a legacy of both wild ancestry and modern agricultural innovation.

The oil palm belongs to the family Arecaceae, a diverse group of monocotyledonous flowering plants known as palms. Its accepted scientific name is Elaeis guineensis Jacq., and it sits within the genus Elaeis. While commonly called the African oil palm, it is distinct from related species such as Elaeis oleifera (American oil palm), and should not be confused with palm-like plants outside the Arecaceae family.

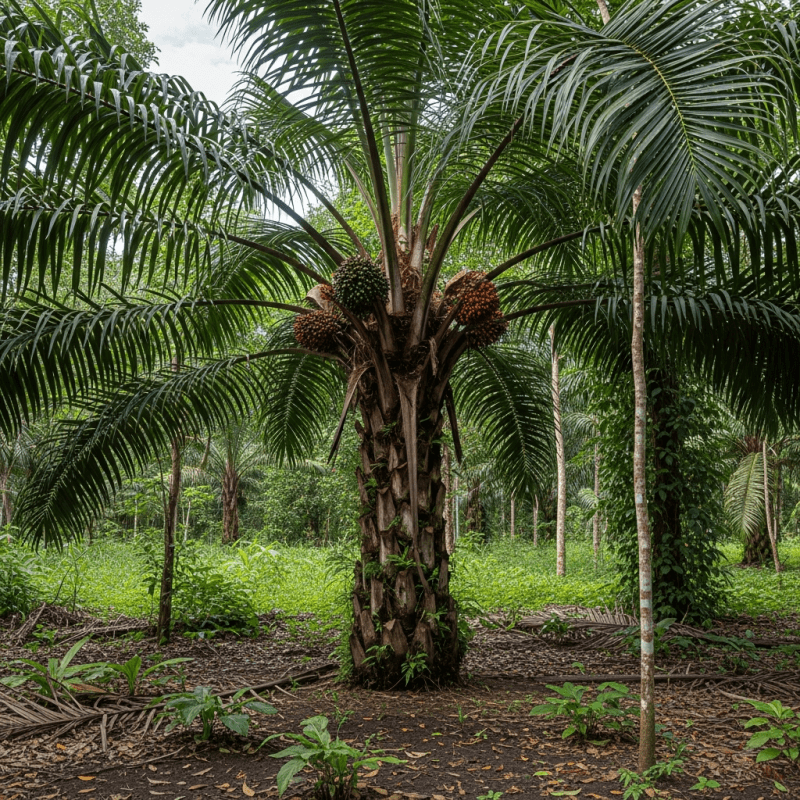

The oil palm is a stately, single-trunked tree that can reach heights of 20–30 meters at maturity. Its crown is adorned with long, arching pinnate leaves—often up to 7.5 meters in length—arranged in a spiral. The tree produces large, axillary inflorescences with separate male and female flowers. The fruit is a vibrant orange-red drupe, typically 3–5 cm long, clustered in heavy bunches weighing 10–50 kg. Each fruit contains a fibrous outer layer (mesocarp) and a hard kernel, both prized for their oil content.

Oil palms thrive in humid, tropical climates and are cultivated primarily for their exceptional oil yield. Commercial harvesting begins just 2.5–3 years after planting, and trees remain productive for up to 30 years. The extracted palm oil is a staple in global food production, while palm kernel oil serves confectionery and industrial needs. Beyond oil, the tree’s leaves and trunk are used locally for construction, thatching, and crafts, making it a truly multipurpose species.

Bring this kind into your world � illustrated posters, mugs, and shirts.

Archival print, museum-grade paper

Buy Poster

Stoneware mug, dishwasher safe

Buy Mug

Soft cotton tee, unisex sizes

Buy ShirtIn West Africa, the oil palm is deeply woven into daily life, cuisine, and tradition. Palm oil is a cherished ingredient in regional dishes, and the tree itself is a symbol of prosperity and utility. Globally, the oil palm has become an economic powerhouse, supporting millions of livelihoods in tropical countries. However, its rapid expansion has also made it a focal point in debates over deforestation, biodiversity loss, and sustainable agriculture.

The genus Elaeis comprises two main species: Elaeis guineensis (African oil palm) and Elaeis oleifera (American oil palm). While Elaeis guineensis dominates global cultivation, hybrids with Elaeis oleifera are increasingly grown in Latin America for improved resilience. Within the broader palm family, there are over 2,600 species, but only a handful are commercially significant for oil production.

Originally thriving in the humid rainforests of West and Central Africa, oil palm now flourishes in tropical regions worldwide. Major cultivation zones include Malaysia, Indonesia, Nigeria, and parts of Latin America. The species prefers consistently warm temperatures, abundant rainfall, and well-drained or waterlogged soils, making it a hallmark of equatorial agriculture.

Oil palms are propagated mainly by seed, though elite lines may be cloned via tissue culture. They require tropical climates, regular rainfall, and tolerate waterlogged soils. Plantations are spaced to allow sunlight and airflow, with commercial harvesting starting 2.5–3 years after planting. Routine care includes pest and disease monitoring, pruning, and fertilization to maintain high yields and healthy growth over their 25–30 year lifespan.

The oil palm is a cornerstone of global agriculture, producing the world’s most widely consumed vegetable oil. Palm oil and palm kernel oil fuel industries in food, cosmetics, detergents, and biofuels. The sector is a major economic driver in Malaysia, Indonesia, Nigeria, and beyond, supporting millions of jobs and generating significant export revenue. Its high yield and versatility have made it indispensable to both local economies and multinational corporations.

Oil palm cultivation has profound ecological effects. While it provides high-yield oil and supports livelihoods, large-scale plantations often replace biodiverse rainforests, leading to habitat loss and reduced wildlife populations. Associated challenges include deforestation, greenhouse gas emissions, and soil degradation. Sustainable practices and certification schemes are increasingly promoted to balance economic benefits with conservation and ecosystem health.

Major threats to oil palm health include Ganoderma basal stem rot and bud rot, which can severely reduce yields and kill trees. Integrated management strategies—such as resistant cultivars, sanitation, and biological controls—are essential for maintaining plantation productivity. Regular monitoring and early intervention help mitigate losses from pests and diseases.

The oil palm’s fruit is its most valuable asset: the fleshy mesocarp yields palm oil, while the kernel produces palm kernel oil. Both oils are edible and widely used in cooking and processed foods. Beyond oil, the tree provides materials for construction, thatching, and local crafts, making it a vital resource in many tropical communities.

While Elaeis guineensis itself is not considered threatened, the expansion of oil palm plantations poses risks to tropical biodiversity and forest ecosystems. Conservation efforts focus on promoting sustainable cultivation, protecting primary forests, and developing disease-resistant hybrids. The species is listed on the IUCN Red List for monitoring, but its greatest conservation challenge lies in balancing agricultural development with environmental stewardship.